39

Consequences

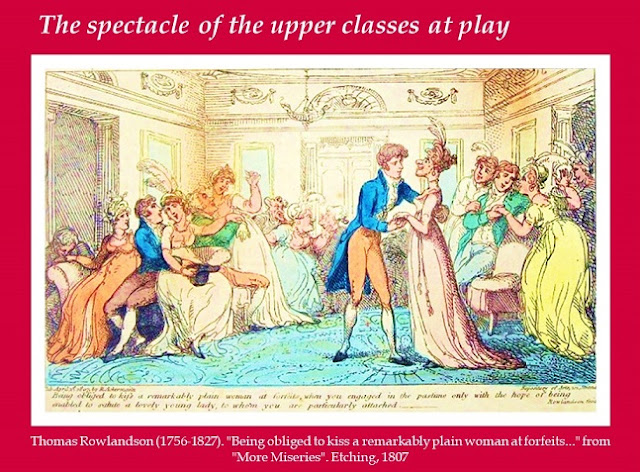

Mrs Urqhart, reseating herself in the ballroom after the supper, noted by the by that the spectacle of the upper classes at play became less fascinating the more you witnessed it, and that lot over there in the corner was a-playing forfeits for what you might expect, and where was Lady Lavinia D. gone off to?

“The card room, I think,” murmured Ned, his eyes on York’s party.

The old lady sniffed, but sat back and silently watched as the Duke of York danced two country dances with the Widder of Willer Court and, after a short interval which deceived nobody, then sat out with her. And subsequently vanished with her.

Sir Ned winced.

“Well, it was to be expected,” she noted.

“Was it?” he returned grimly.

“Lord, is you jealous?” she said on a scornful note.

“I— Not precisely, no. But I cannot help wondering whether she knows what she is letting herself in for.”

“Well, if she don’t, His Highness will no doubt draw her a picture.”

Ned bit his lip, and fidgeted.

After a little Mrs Urqhart, seeing he had not said anything further, noted: “That hanger-on, Slingsby or whatever he calls himself, went with ‘em.”

“Yes, but one is told that that is the usual practice with the princes, and then the—er—the third party withdraws.”

“You don’t tell me!”

Ned bit his lip again. “Well—well, where does that door lead to?”

“A passage, with two little withdrawing-rooms. Don’t think they is bein’ used for anything. In particular.”

He bit his lip again. There was another pause.

“Go on then, chase after her, make a bigger fool of yourself than what she is,” she recommended.

“She cannot be aware— I dare say she intends no more than mere light dalliance.”

“She!” said Mrs Urqhart with a laugh.

Ned hesitated. “Possibly he will not insist, if she—if she—”

“Aye, and possibly that Slingsby is a-standin’ outside the door of one of them little rooms, a-makin’ sure if he does insist, there won’t be nobody around to tell the tale! Lord, Ned, you is gone loony!” she gasped as he rose abruptly.

“No doubt. But please excuse me, Betsy.” He strode off.

Mrs Urqhart gave a sigh that was almost a groan. And was not much mollified by the sight of Johanna going happily down the dance with Mr Dorian.

Evangeline had not been much disturbed by the Duke of York’s putting his hand on her thigh at supper, for she was not unused to naughty gentlemen who did just that and, in the furtherance of her late husband’s career, had endured more than one of them. She was not, however, particularly stirred by it, for he was a gross and not young man. But she was certainly very pleased that it was herself on whom he had chosen to bestow his flattering attentions, and flirted with him as much as His Royal Highness could have desired. After considerable low-voiced converse, with the exchange of many meaning glances and silly laughs, she allowed him, as observed, to lead her out of the ballroom. For Muzzie had now been taken under the wing of Mme Girardon herself, and— Well, it would be exciting beyond anything to be kissed by a Royal personage—though not exciting in that way, of course—and it would be something to tell over to herself in the solitary hours of her widowhood in isolated Willow Court. And truth to say, the amount of champagne the Duke had jovially forced upon her had made her reckless. So she had gone.

She had not for a moment believed that Slingsby would remain with them, and was neither surprized nor disturbed when he left them, on a murmured excuse. The Duke immediately urged her to be seated on a small sofa. Blue brocade, very pretty, it chimed charmingly with the shade of her dress, and Evangeline was quite happy to sit down on it. York wedged his substantial form beside her, smiling.

“All this fuzzy stuff is dashed attractive, I declare!” he then said, touching the puff of her sleeve. “You naughty ladies do it on purpose to drive us poor fellows to distraction, do you not, ma’am?”

Lady Charleson could deal very easily with this sort of repartee, in fact dealing with it was meat and drink to her, so she gave an arch smile and replied: “Oh, sir! How can you accuse a poor widow of such low designs! I declare, it is you who is the naughty, naughty one, in this instance!”

“Rubbish, dear lady,” he said, a trifle thickly, fingering the lace again. “Fuzzy—very pretty.” His fingers touched the arm through the lace; she jumped. “Aye, aye, you are a hot little filly!” he said with a deep chuckle.

“Sir!” she protested, but flicking him a glance from under her thick lashes.

Greatly encouraged, His Royal Highness slid one arm along the back of the sofa. The other hand continued to fondle the upper-arm through the lace. “Mm, a hot little filly,” he repeated pleasedly.

“On the contrary, I am a respectable widow,” she said with dignity.

His hand closed firmly on her arm. “Aye, you know what it is all about, do you not?”

“Sir!” gasped Evangeline in pretended outrage.

He chuckled again. “Why, what else is all this fluff and all this blue filmy stuff over this fine skin for, if not to entrap us helpless fellows, mm?” He began to knead the flesh, very slowly.

Even though Evangeline did not truly desire him, the sensation was not unpleasant to her. She swallowed loudly.

“Mm-mm,” he said on a long-drawn note, running his hand down the whole length of her arm, and taking her hand in his. “A great pity you are not one of the house-party, my Lady.” He turned the hand over and kissed the wrist.

“I am sure I do not know what Your Royal Highness means,” she said weakly.

Smiling, the Duke ran his hand back up the arm again, rather more on the inside, this time. “Silk,” he said pleasedly. “All silk and fluff: a poor fellow is nigh driven distracted by you, my Lady.”

“You flatter me, Your Royal Highness,” she murmured.

“No, no, no: that would be impossible, my Lady! Why, you are the colour of a Dresden figurine, and softer than the finest silk!” At this the hand slid from the arm onto the bosom, and stroked it, over the lace, back and forth.

“Oh—please!” said Evangeline with a little gasp, fluttering the lashes wildly.

Not unnaturally the Duke of York took this for encouragement and got the hand right in under the lace. Evangeline was conscious of a strong wish he would not tear it. And also of a strong wish he were not so old and fat.

“What have we here?” he said with a chuckle, now turned right around on the sofa so that his face was very close to her neck. “I declare, two little silky feather cushions, you have under this lace!” The hand slid down—the silk underdress was cut so low it did not have far to go—the fingers touched a nipple, and Evangeline gasped. Highly encouraged, the Duke then pressed his face to hers and kissed her, warmly and wetly.

Evangeline first gasped, then responded.

He nibbled her ear a little, and she gave a little squeak; he took his hand out of her bodice and fondled her breasts much more strongly, and slid it down over her belly, and she gasped again, and said weakly: “No, no, sir: pray—!”

The Duke was entirely used to such encouragement: he kissed her eagerly and then buried his face in her bosom, making strange grunting noises.

Evangeline was just a little frightened, for after all he was a large, strong man, and she was all alone with him—but then, Royalty would hardly do anything utterly beyond the pale—

And then she realized, as he covered her mouth with his, and pressed her back strongly into the sofa cushions with a lot of his weight on her, that the grunting noises and the writhing motions of his body indicated that His Royal Highness was getting himself out of his knee-breeches!

“No!” she gasped, wrenching her mouth away. “Sir, pray stop!”

“Nonsense,” he said thickly, forcing his mouth back onto hers. “Don’t be Missish, my dear, it don’t become you.”

Evangeline pulled away again as he said this last and hissed: “Sir, I do not wish for this! You are mistaken! Release me!”

“Rubbish, hot little filly like you!” he panted, kissing her again. “You’ll enjoy it!”

“No!” she gasped, pulling away.

The Duke covered her mouth again and began fumbling at her skirt, rolled almost entirely on top of her.

“No! Stop!” she cried, as he drew breath. “Please!”

“Rubbish, my Lady! Come, one more kiss and then I’ll—”

“NO!” she screamed. “Let me GO!”

It was doubtful that he would have let her go, since he was almost over the last hurdle, in fact the gown was up to her waist, but Evangeline was never to find out, for at that moment there was a sort of thumping noise from outside the door, the door opened, and a cool male voice said: “I trust I do not intrude?”

“Oh! Sir Edward!” she wailed. “Make him stop! Truly I don’t want to!”

“I gather the lady does not wish to, Your Royal Highness,” said Ned unemotionally.

“No! I thought he only meant to kiss me!” gasped Evangeline, bursting into tears, as the Royal personage, very ruffled, and puffing, and spluttering something about “the door” and “Slingsby,” and “dammit, hot for it” attempted to get his Royal person back into his breeches.

“I think Slingsby must be the gentleman recumbent on the floor of the hall as we speak,” noted Sir Edward, as Lady Charleson, freed of His Highness’s considerable weight at last, rose and threw herself at him.

“It was all a damned mistake!” said the Duke angrily, having finished stuffing himself into his breeches.

“I quite understand, sir. Provincial ladies with as little sense as they have experience can be very silly indeed,” said Sir Ned, still unemotional.

“Aye, that is it,” he muttered. “Why, I meant no more than a kiss and a cuddle, and she— Well, she led me on, you may believe what you like, sir, but she led me on!”

“I know she did,” he said calmly. “I saw it.”

This was not precisely what the Duke had meant but he said hastily: “Aye, well, there you are! Any fellow would have thought—”

“Indeed. Perhaps Your Royal Highness would care to leave the lady to me? I shall calm her down,” he said, as she sobbed on his shoulder.

“Er—yes,” he said, coughing. “Very well. Say no more about it, hey?”

“I certainly shall not, you may rest assured, sir.”

“Er—well, yes, quite. Be goin’, hey?”

Ned merely inclined his head.

York got himself out of the room and though he closed the door, could then be heard shouting at Slingsby to get up, he was not hurt, and what the Devil had he meant by sayin’ the woman was hot for it, and— Their voices faded away.

“He was horrible!” cried Evangeline loudly, momentarily ceasing to sob. “And—and I did not lead him on, how dared he— And how dared you?”

“Of course you led him on, poor stupid fellow: he may be venal but he is not a monster. But has no-one ever told you that he ain’t a gentleman, either?” he said drily.

Evangeline gulped. “I thought he only meant to kiss me.”

“Aye, I realise that. And you thought it would be fun to be kissed by a Royal duke. Well, it wasn’t, was it?”

“No!” she cried loudly, bursting into tears again,

Ned led her sobbing form to the sofa and gently pressed her onto it, giving her his handkerchief.

Evangeline sobbed for some time. He made no attempt to comfort her, or to touch her in any way. Finally she blew her nose, not looking at him.

“Well, you have made a damn’ fool of yourself, have you not?” he said calmly.

She glared at him over the handkerchief.

“Of course, he has made a worse one, but unfortunately Society don’t condemn men—and certainly not Royalty—for that sort of thing,” he said mildly.

“What do you mean?” she said in a shaken voice. “No-one knows of it but ourselves! Surely—”

“Surely you don’t imagine that that toady, Slingsby, won’t spread it all round the house-party that you granted his master the favours that only we know you denied him?”

Her jaw dropped.

“Oh, yes, he would,” he replied to her unspoken protest.

“Stop him, Sir Edward!” she gasped, turning very white.

“I’m afraid that is beyond my powers.”

“Buh-but— There must be something— My God, I am ruined!” she gasped.

“More or less, yes. I must suppose it will become known in the neighbourhood. Though this lot at the house won’t be all that much interested in a provincial lady’s losing her virtue to a Royal prince, it’ll be less than a nine days’ wonder to them. But that won’t mean that word won’t get around.”

“No. What can I do?” she said through trembling lips.

Ned scratched his curls. “I think you had best come to Paris with me.”

“What?” she gasped.

“I have a nice little house there, overlooking the Parc Monceau, a pleasant area. Fortunately the late conflict turned out as it did: I would not have liked to lose it,” he added in a thoughtful tone.

Evangeline just stared at him.

“I do considerable business in Europe,” he explained. “Paris is quite a convenient base.”

“You— A house near— Is this a proposal, sir?” she croaked.

“Well, no. Say, rather, a proposition,” he replied, still thoughtful.

“A prop— How dare you!” she gasped, bolt upright.

Ned sat down beside her, not very close.

“I have not done anything wrong!” she cried.

“Well, nothing very much—no. How unfair life is,” he said, still thoughtful.

“I cannot possibly become your mistress!” gasped Evangeline, trembling.

“What is the alternative? To be shunned by such as the Purdue female and dwindle away into an old woman in that ramshackle house of your son’s?”

Her mouth opened and shut. Finally she said in a voice that shook: “I have the children to consider. It would be impossible. Muzzie has attracted the favourable notice of a very respectable gentleman and—and his papa and mamma would never permit a match if—if we—”

Ned scratched his curls again. “Well, no. What if this story gets to their ears, though? And don’t say it won’t: Grey is a friend of Lucas Claveringham, and he and most of his family are here tonight. And I should not think Master Luís Ainsley and his ilk will hold their tongues, either.”

Evangeline was again very white. Her hand went to her mouth and she peered over it at him with frightened eyes.

“Well, I am glad to see you thinking of little Muzzie at long last,” he said mildly.

“Yes,” she said faintly behind the hand.

Silence fell in the pretty little salon. Ned scratched his curls again. Evangeline stared numbly before her, her hands fallen into her lap.

Finally he said: “I’ll speak to Lord Rockingham, though I don’t think he’ll be able to scotch the story. But at least I can see that he and his family know the truth. And the Ainsleys, also. And I’ll write to Major Grey, tell him how it was.”

“Thank you,” she said faintly.

“The cats will still shun you, however. And I would not advise London, next year.”

“No. Faith may bring Muzzie out. I shall stay here and—and help Eric to get the estate into order. Uncky Charleson has been urging me to, this past— Well, at any rate, it needs to be done.”

Ned thoroughly agreed with this. He did not say, was it not too great a sacrifice on her part, though he felt like it. He got up. “Well, I think that is the best that I can do. Come, you had best see to your face. I shall find Eric and see you go straight home. –Your Cousin O’Flynn is not staying with you, I think?”

“What? Oh—no, he is at the Manor. Thank you,” she said, suddenly going very red and staring at the floor. “I— You must think I am a loose woman.”

“No. A loose woman would have done what the right Royal idiot expected of you. I think you’re a damned silly one, that’s all.”

“It is not fair!” she burst out. “Men may—may do anything, and—and... Women are not expected even to have feelings!”

“I know that,” said Ned, feeling considerable sympathy, which he did not allow to show. “That’s why the Paris offer still stands.”

She gulped.

“Come along,” he said unemotionally, taking her elbow.

Silent and red-faced, Evangeline allowed him to usher her out.

“Shall we go?” said Ned, when he eventually returned to Mrs Urqhart’s side.

“Eh? You is stayin’ here, you gaby!”

“Er—no. I have thanked Lord Rockingham and told him—er—that I shall be spending a few days with you.”

“What happened?” she gasped.

“Er—well, for the nonce, Betsy, let’s just say that my continued presence here might embarrass a certain—er—august personage.”

“You punched him in his stupid fat face!” she gasped, eyes lighting up.

“Regretfully, no. I did floor the toady, however.”

Mrs Urqhart’s eyes sparkled, but she said: “Me love, if you would not mind so very much, I’d like to stay on, just to see the last of the dancing. Mrs Girardon was sayin’ the country dances is done, and there is but two waltzes to go, now.”

“Very well. –Would you care for a turn on the floor?” he suggested.

“Aye, well, if you floored the toady, you deserves a reward! Only wouldn’t it be infinite better with Someone Else?” she said, her eyes on Hildy’s fairylike person in her floating white, in a group with her sisters and cousins.

“I have put that absolutely out of my mind,” he said on an odd note.

“What have you done?” she gasped immediately.

“Er—nothing. Well, not very much. I shall tell you about it directly we are alone, but not here. –Shall we?” he said as the musicians struck up.

“Hang on,” she replied tersely as Jo came up to them on Dorian’s arm.

“Aunt Betsy,” she said: “Mr Dorian would so much love a waltz with you, if you would permit him. While I would so like a dance with Papa.”

“I think I might force my creaky old person to take a turn,” replied Ned, smiling. “In fact we were just saying we might venture onto the floor.”

“Good!” said Jo, beaming.

“Splendid!” agreed Dorian, bowing very low before Mrs Urqhart. “Shall we, ma’am?”

“Well, I dare say me supper has sunk sufficient’“ she said, chuckling richly. “Only don’t you go too fast round them corners, mind!”

“Certainly not, ma’am!”

She looped her train up, and they glided away, not very fast. In fact not as fast as the music, Ned noticed, mouth twitching. He held out his arms to his daughter, smiling, and they also glided away.

“Nice,” he said, after a little. “That Mounseer would be proud of you, my dear!”

“M. Maréchal. Would you believe his real name is Robert Bruce Marshall, Papa?” she choked.

“Aye, I would! For I have never heard such a Scotch French accent in all me days!” he gasped.

They smiled, and danced in silence for a while, very pleased with each other. Eventually Ned said: “Thank God I persuaded Betsy it would be the thing for us to buy you that deep apricot gown, my lamb. It becomes you. Especially with those russet velvet ribbons.”

“Yes: even Sir Julian Naseby, who of course has exquisite taste,” said Johanna, laughing a little, “congratulated me on the combination!”

“Good. And Mr Dorian Kernohan?” he said, smiling slyly.

Jo blushed and said in a low voice: “He was very complimentary.”

“Good,” he said, squeezing her hand.

They danced on.

“Papa,” said Jo timidly: “something has happened, has it not?”

“Er—mm. Well, I shall tell you about it later, my pet, for you are not a simpering Miss, thank the Lord. Only it is not something that will affect you. Or us,” he added, squeezing her hand again.

Jo swallowed. “No. I—I could not but see that Lady Charleson did not return to the ballroom and—and that Mr Charleson looked very startled when you spoke to him and—and that he fetched his sister and went out... Papa, if—if the poor lady should have done something foolish and—and need rescuing,” she said, gulping, “please don’t let me stand in your way.”

Ned hesitated. Then he said: “You are very generous, my lambkin. But I am not thinking of remarrying, at this point.”

“No,” said Jo, very faintly.

“I should like one Season in our house in London, with just my little daughter for company, before I make any changes in my way of life!” he said, with a little laugh.

She looked up at him gratefully. “Oh, so should I, Papa!”

“Good. We’ll talk it all over later, but that is what we shall do, then.”

Johanna sighed, and he held her close and breathed in the scent of her clean, dark hair, and thought vaguely of his little Fanny, and then permitted himself the luxury of not thinking at all, for the rest of the dance.

Hildy and the Major had not so far danced. But they had sat out several of the country dances, not in a fashion to be remarked, but sometimes in the company of Mrs Maddern and Cousin Sophia and sometimes of Mr O’Flynn and Amabel. They had chatted on a great variety of topics, nothing particularly controversial or meaningful, and had both felt quietly happy.

When the waltz struck up the two couples were seated in the company of Major Kernohan’s youngest brother as well as Mrs Maddern and Mrs Goodbody. Mrs Maddern, having capably dispatched Amabel and Mr O’Flynn to the floor, rose, saying: “Come along, Mr Roly, there is a poor young lady over there without a partner.” She led him off to lay him at the feet of the gratified young lady.

That left Hildy and the Major, with Mrs Goodbody.

“Should you care for it, Miss Hildegarde?” he said. “I would very much like to, if it would not discommode you?”

Cousin Sophia was nodding and beaming. Hildy gulped, and managed: “Thank you, Major Kernohan.”

“Can you help me?” he said simply.

“Yes.” He had raised his arm a little: Hildy took his hand and placed it at her waist. The Major took her other hand in a firm grasp and twirled her away. Immediately Mrs Goodbody whisked out her handkerchief.

Mrs Maddern returned, looking very pleased.

“It worked, Patty,” said her cousin, sniffing, and stowing the handkerchief away.

Mrs Maddern nodded. “Good. –The poor boy,” she added softly.

Cousin Sophia blinked rapidly. “Sí. –Oh, my land, now I am doing it!”

The two ladies looked at each other, and laughed. After which they returned their concentration to the dance floor.

Once he had Miss Hildegarde in his arms Aurry found that the mood of quiet happiness which had prevailed while they chatted had quite vanished, and was replaced by a great pounding of the blood. He was incapable of speech for quite some time. So, apparently, was she. Finally he said, or rather croaked: “Have you enjoyed the ball?”

“Not very much,” replied Hildy bluntly.

“Oh. You appeared to me to be having a very pleasant time,” he said blankly.

Hildy swallowed. “I suppose I did not lack for partners. And I do quite enjoy to dance. But most of my partners were very silly.”

“Silly?”

“I could not talk to them.”

There was a short silence.

“One would not have guessed,” said Major Kernohan, not having intended to say any such thing, and even as the words left his mouth wondering what in Hell was wrong with him, “that you found your partners silly. On the contrary, you appeared to be enjoying every dance.”

“I see,” she said, looking up at him with big, serious eyes. “You mean I flirted with them.”

Aurry blinked. “Er—”

“There is no sense in not calling a spade a spade. I know I am a flirt. But I only do it with gentlemen who are not serious, either. –At least, I try to,” she said, frowning, as she recalled those months when she had not known whether or not to encourage Sir Julian.

“Mm. And sometimes, I suppose, the gentlemen make it very difficult not to?” he said on a kindly note.

“No’,” said Hildegarde, firmly looking up into his face still. “What makes it so difficult is that sometimes I am attracted to the gentleman, sir.”

“Oh,” said Aurry lamely, feeling as if his stomach had fallen into his boots.

“And if a person is like that, it is very hard to—to understand one’s own feelings,” she said, swallowing. “And—and recognize what is true feeling, and what is not.”

“I understand exactly what you mean. Thank you for telling me,” he said stiffly. He felt her little hand shift nervously in his. “What is it?”

“Major,” said Hildy with tears in her eyes, “I think you have misunderstood me. I did not mean that—that I am incapable of true feeling; only that I have—have made stupid mistakes, in the past! But now I know better.”

Suddenly his heart soared. He gave a tiny laugh and pulled her to him, too absorbed to reflect that that was not proper at all, and said: “Well, we all make stupid mistakes! And I think I very nearly made one then. But now I do understand.”

“Yes,” said Hildy, very softly.

They completed one full circle of the big room with Miss Hildegarde clasped very improperly to the Major’s chest. Then he loosened his hold a little and said, smiling into her face: “Tell, me, if it is not a great impertinence in me to ask it: was Sir Julian Naseby one of the mistakes?”

Hildy gave a little shudder. “Yes, indeed! Really, the worst mistake, because with the other gentlemen, I quickly realized that we should not suit, or that—that it was ineligible.”—The Major had to bend his head to hear her: she was speaking very low into his waistcoat.—“Only he is such a very pleasant person, and—and he would not be discouraged for so long... And I began to think that perhaps it might do. But when he came to Bath, I saw that it would not, and it—it would have been dreadful!” Suddenly she looked up at him, her eyes full of earnest tears.

Major Kernohan was not so innocent as she, and he did not think it would have been that. But he did think that after a few years the pleasant and fashionable Sir Julian might well have begun to grate upon the nerves of a bright little lady who found the majority of the pleasant young fellows at the Daynesford Place ball “silly” and unable to converse. “I am very glad you realised it,” he said steadily.

Hildy blushed and looked away. They completed another tour of the room in silence.

“Miss Hildegarde,” said the Major in a very low voice, “would it displease you if I—if I came to call?”

“No,” she said blushing brightly but looking into his face. “I would like it of all things, Major.”

Aurry’s blood pounded furiously again. But he said merely: “Good,” and pulled her to him again.

When the dance ended she looked up at him dazedly.

“Come and sit down,” he said huskily.

“Yes. Thank you.”

They sat down on two little hard chairs. Hildy felt too shy to speak, and also much too excited: her heart was thumping terrifically and for a moment she wondered if he could hear it, it was so loud.

The Major began to talk about his house and his property. Hildy had to force herself to listen. Eventually she was able to concentrate on details. But it was not until the dance taking place on the floor before them had ended that it dawned on her that he was laying such stress on how long it would take before the place was habitable and the kitchen garden producing anything because—because— Her hands trembled and she blushed brightly and looked up at him helplessly.

The Major had been explaining that most of the orchard would shortly be ripped out. “Er—what is it?” he said cautiously.

“Oh! Nothing!” she gasped. I mean— Well, Higgs says that sometimes if you chop an apple tree right back, it comes on like nobody’s business!”

“Does he? That is the head gardener at the Manor, is it?” he asked, smiling. Hildy nodded and he said gaily: “Well, in that case, when I come to call, you shall introduce me to him, and perhaps he will be good enough to give me the benefit of his good advice!”

“Oh, yes!” she cried. “And I shall have all Dr Rogers’s botanical books sent over from home, I shall not wait until we move into the dower house, and we may consult them immediately!”

Major Kernohan did not find anything to cavil at in this coupling of their interests. On the contrary. His lean cheeks flushed brightly and he said: “Indeed we shall. And now I think I had better take you back to your mamma.”

He did so, and bowed very low over her hand, kissing it lightly and properly. “I shall see you very soon,” he said, under the eyes of her mesmerized relatives.

Under the eyes of her mesmerized relatives Miss Hildegarde blushed brightly and said in a tiny, shy voice worthy of her sister Amabel: “Oh, yes, Major!”

After quite some time Mrs Maddern managed to say: “Now—now, are we all ready? Come along, my dears.”

“But where is Gaetana?” said Hildy, looking round her dazedly.

“Never mind, my dear, she and Harry and Marinela may follow along behind us! Come along!” said Mrs Maddern briskly.

Gaetana had been hiding for some time behind a heavily swagged pillar. There had been a waltz, in amongst the country dances, and not only had Lord Rockingham not appeared to claim her for it as promised, he had not even been in the ballroom at the time! And when he had come back he had been with Sir Edward Jubb and they had talked together for some time and he had not even glanced her way. So he had just been teazing. Or flirting, or something equally stupid. And she wished she were dead!

… “Where is she?” demanded the Marquis in exasperation, running his hand through his black curls.

“Giles, poor Sweet spent I dare say as much as an hour combing your hair into some sort of elegance, and now look at it!” replied his mother with a gurgle.

“Eh? Oh—damn, what a fool,” he said, grinning ruefully. “Now I dare say she will not smile upon me, at all. But where has she got t— By God, if that clown Welling has her again, I’ll—”

“No, he is with her aunt and cousins,” she replied calmly. “Giles, what were you and Sir Edward Jubb conferring about a little earlier?”

He made a horrible face. “I shall tell you later, Mamma, I promise. But not here.”

“Very well, my dear. Perhaps it would not be inappropriate to mention at this point,” she added, “that that horrid Slingsby has been going around dropping words in various gentlemen’s ears.”

“Aye, damn his eyes, the slimy little rat! And I’ll be damned if I invite York to my house again, for ten Sir Harrys!” he said with feeling.

“Ssh! But you did not do it for ten Sir Harrys, nor even for one, did you?” she said slyly.

“No. And where is she?” he demanded.

“Well, I cannot see her, but I found her hiding behind a pillar a little earlier. Suppose we circle the room,” she said calmly, taking his arm.

After a moment he muttered: “I wish I had not had this damned party.”

“Er—well, I suppose it has served to demonstrate that neither York nor Wellington is averse to Harry Ainsley’s company, my dear. If that is what you wished to demonstrate?”

“Of course!” he said angrily. “And the Lievens, and the Seftons, and the rest of ’em!”

“Mm. Well, Lady Hubbel actually voluntarily addressed Lady Ainsley, a little while back. That must count as a signal triumph, indeed.”

“Mamma, it is not a joke!” he said tightly.

“No, my dear,” Anne agreed, hugging his arm. “Merely ridiculous.”

“What more could I do?” he said angrily.

“Jean-Pierre, Hugh and I are agreed that less, rather than more, would have been indicated.”

“Aye: I should not have had damned York. –I knew we should never have invited the damned Charleson woman, and so I told Lavinia!”

“Dearest, that was because you feared she might capture pleasant Sir Edward,” she murmured. “And we should not be talking of it, here.”

“No,” he admitted, grimacing. “Just wait until the question of the Civil List comes up before the House!” he added grimly.

Mme Girardon winced, but said nothing.

“Where the Devil is she?” he muttered.

“Patience, my love,” she murmured, nodding kindly at a cluster of gossiping dames.

“Ten to one they have got the story, already,” he muttered.

“No, I do not think so, their expressions are not of prurient delight,” returned Anne calmly.

“Mamma, I wish to God you would reconsider coming to England to live!” he said fervently.

She laughed a little. “At the moment Jean-Pierre is very much occupied with his bees.”—“Bees,” he groaned.—“We shall wait and see how it is when Carolyn marries. Should she marry an Englishman, I think he may wish to remove. He has missed her very much these last few months.”

“Well, thank God for that!” he said, beaming. “Oh, there she is!” he added. He hurried up to Gaetana, beaming even more.

Mme Girardon could see that Miss Ainsley was looking angry. She said nothing, but followed slowly.

“Miss Ainsley,” said Rockingham eagerly: “I believe this next is our waltz?”

“Then you are mistaken in your beliefs, my Lord. It is not our waltz. The first waltz after the supper went by quite some time past.”

His jaw sagged.

Mme Girardon hastened to heal the breach. “But Giles had a duty to perform at that time, Miss Ainsley. Pray do not condemn him for that.”

“A duty!” she said angrily, glaring at the Marquis.

“It—it was a matter of—of endeavouring to scotch a scandal,” he said uncomfortably.

“That is quite correct, my dear: it was a matter of a lady’s reputation, and though we shall not discuss it here, I can assure you that Giles would not have been absent from the ballroom for anything less serious,” said his mother calmly.

“Oh,” said Gaetana numbly.

“Now,” said Anne, with her attractive little gurgle of laughter, “since poor Mr Sweet spent at least an hour this evening arranging Giles’s curls in a fashionable style, and I dare say wasted a score of neckcloths before achieving a perfect Mathematical—not that one would perceive it as of now, for he has since rumpled the curls and tugged at the neckcloth—could you not gratify the poor fellow’s heart and allow Giles one little waltz?”

“Who is Mr Sweet?” said Gaetana numbly.

“My man!” he said with a laugh. “Cummins’s greatest enemy! –When they ain’t plotting together against me for me own good, of course. I’m the blight of his life.”

“Yes, well,” she said, rallying somewhat, “that does not look like a Mathematical to me. Not if what Lord Broughamwood is wearing is such, as Mr Charleson and Luís have both assured me.”

“Aye: niffy as nothing, ain’t he?” he said with a laugh. “Not a well man, though, poor chap,” he added, shaking his head. “Now, if you please, you cannot be so cruel!”

Gaetana opened her mouth.

“And all Sweet’s work cannot go for nothing!” he added.

“I am very tempted to send you to the rightabout, Marquis,” she said weakly.

“No, do not do that, I beg, my dear, we have another week of this dreadful house-party to get through,” said his mother, smiling, “and with Giles like a bear with a sore head it will be quite unbearable!”

“‘Bear’—‘unbearable’, Mamma?” he said, grinning. “Will you, Miss Ainsley?” he added, holding out his hand.

Gaetana had been going to say something cutting but found herself instead saying in a tiny voice: “Thank you.”

The music had started: he led her onto the floor.

After a few minutes he said in a shaken voice: “Is it you trembling or I?”

“Me,” she croaked.

He held her much more closely. “No, it is I as well. –Is that better?”

“Yes—no,” she gulped.

“Did you think I had forgotten you?” he murmured.

“No!” said Gaetana crossly, swallowing.

“Liar,” he returned, smiling. “Of course I had not forgotten. Why, this whole damned charade is for you, you must be aware of that!”

After a moment she said faintly into his waistcoat: “So you admit it?”

“Yes, of course! I told you your papa would be received in the highest circles, and though I’ve since changed my mind about damned York, Wellington is most certainly the highest!”

“Yes,” she agreed faintly.

“Now do you admit you were very silly?” he said into her auburn curls.

“No. At least—there is a moral principle at stake, sir.”

“Well, possibly there is. But I thought the whole problem, Miss Ainsley, was on the contrary, a question of stupid social forms? Not to say accursed toad-eaters? And now I have now demonstrated to you that, worthless and empty-headed though the Upper Ten Thousand undoubtedly are, even the most particular of them will receive your papa with equanimity. –Well, you can’t get much stiffer than the Countesses Hubbel and Lieven, for God’s sake!” he added impatiently.

Gaetana smiled a little. “No. We like Lady Hubbel’s daughter, Lady Jane Claveringham, however.”

“Aye: I saw her getting on like a house on fire with Miss Amabel,” he agreed.

“Mm. But sir, possibly these people have—have behaved with such complaisance towards my papa and mamma only because they would not care to do otherwise, under your roof?”

“Your mind is too damn’ sharp for your own good, Miss Ainsley,” he noted ruefully. “That is certainly a possibility with some of the damned toad-eaters that jumped at the invitation, I’m not denying it. But I did not invite the Lievens, the Seftons or any of the Claveringhams without mentioning who would also be present tonight; it would have been neither kind nor sporting.”

“No,” she gulped. “I see.”

“That is not a lie, Miss Ainsley,” he said calmly.

“No!” she gasped in horror, looking up into his face. “Of course I did not think you would lie to me!”

“I’m relieved to hear it,” he said, twinkling at her. “So you think I’ve ruined poor old Sweet’s beautiful neckcloth, eh?”

“What?” she said in confusion. “Oh! Oh—well, yes, I am afraid you have. And that very lovely pearl pin is—is not where it was when you received us earlier this evening, Marquis.”

“Fiddled with it: was feelin’ nervous,” he confessed, grimacing.

Gaetana went very pink and looked fixedly at the top of his waistcoat.

“You are looking very pretty,” he said gruffly.

She swallowed.

“You always do. –I’m not a pretty fellow,” confessed his Lordship glumly.

She looked up at him doubtfully and saw he was not funning. “A—a gentleman does not have to be. And—and Mrs Goodbody finds you most Byronic, sir!” he added desperately.

“Good gad! –Look, come and sit on this little sofa, can’t talk during a dance,” he said, suddenly leading her off the floor.

The little sofa was rather secluded, being almost concealed on the one hand by one of the swagged pillars and on the other by an huge china vase on an even huger china stand, the former filled with exotic blooms which managed to reflect not one of the many colours in both stand and vase. There were about two dozen of these stands round the sides of the ballroom and Lady Lavinia had found herself compelled to explain at several points during the evening that they did not form part of the room’s original décor.

The Marquis sat Gaetana down at one end of the sofa and took up a position at its other end, turned to face her, one arm resting casually along its back. He could have touched her with very little effort and Gaetana was very conscious of the fact.

“As I was saying, that is a very pretty dress,” he said, looking at her pale green gauze with its green satin sash and knots of ribbon in the flounce at the hem.

“Harry said it was too plain,” she returned blankly.

“Got no taste. Told me the ballroom looked very fine,” he replied simply.

“But it does,” said Gaetana weakly.

“No, both Mamma and Lavinia have told me I should never have given the staff their heads with it,” he explained glumly.

A slow smile spread over her face.

“What?” he said with foreboding.

“They are hen-pecking you!” she choked delightedly. “Oh, how perfectly splendid!”

“Aye, well, I must say Carolyn feels she is getting some of her own back for those weeks when I didn’t drive her into Ditterminster to do the pretty to the damned Bishop’s wife,” he admitted, grinning.

Gaetana smiled. “Indeed!”

Then there was a short pause. Gaetana looked at her hands in her lap and Rockingham looked at her.

Finally he said: “You could wear emeralds.”

Gaetana took a deep breath. “Lord Rockingham,” she said firmly: “did you lead me to this sofa in order to tell me I could wear emeralds?”

“Actually, I did not.”

“No,” said Gaetana, swallowing.

“Have I proved to you that your scruples were nonsense?” he said in a very low voice.

At this point a truly principled young woman—Elinor Dashwood, quite undoubtedly—would have reiterated the point that it was the moral matter that should concern them. After a moment Gaetana found herself saying weakly: “The Duke of Wellington certainly was most gracious to Pa and Madre, and to me.”

“Yes. Well, any man with red blood in his veins would not be less to you or Marinela. But I agree, he spoke very kindly to Harry. –Well?”

Gaetana’s hands trembled. She clasped them very tightly together. “I—I suppose you have proved your point.”

The Marquis passed his hand over his face. “Thank God for that,” he muttered.

She looked at him doubtfully. His hand was hiding his face. “I did not wish to cause you pain,” she said, very faintly.

“No,” he replied with difficulty.

There was silence between them.

After a moment Rockingham felt a gentle little touch against the hand that was shading his face. He jumped very much and took the hand away to find a little wisp of lace and cambric was being offered him. “Thank you,” he said shakily, wiping his eyes.

Gaetana was terribly upset. She had not truly believed that he would be hurt so much. His proposal to her had been so— Well, he had spoken so light-heartedly! She was overwhelmed by the recognition of all he must have felt, and remembered her own sleepless nights and all the times she had been overcome by despair and cried into her pillow.

“I will,” she said in a tiny gruff voice.

“What?” he returned, sniffing.

Gaetana gulped. “I will. Marry you. If you still wish for it.”

Rockingham swallowed. “Does the thought of being immured in my house with me no longer scare you, then?”

“Yes, it does, a little bit,” she said honestly, very flushed. “Only—only I cannot bear to see you suffer.”

“Oh,” he said limply. “I suppose that is laudable.”

“I did not express that very well… What I meant was,” said Miss Ainsley, looking up into his face with painful earnestness, “that I wish to spend the rest of my life comforting you, not giving you pain. –Oh, dear, I’m not putting it right! I mean I wish to look after you!”

“So you think I need looking after?” he asked, smiling shakily.

“Sí,” she said timidly.

Rockingham picked up her hand and kissed it very gently. “You are right. Will you come and live in my house and comfort me and look after me and prevent my relatives from hen-picking me and me from jockeying you into things you do not wish to do and bullying you unmercifully, Gaetana?”

“Sí,” she said, sniffing. “I said.”

He gave a tiny laugh that cracked, and returned the handkerchief to her. Gaetana blew her nose hard.

“Good,” he said. “Goddammit,” he realised, “I suppose I’d better speak to Harry!”

Gaetana laughed shakily. “You’re not very good at doing things properly, are you? From neckcloths to proposals!”

“Aye: carelessness. My besetting sin,” he said, grimacing. “You’ll have to look after that!”

“Sí,” she said smiling and blushing. “I shall, my Lord.”

“And one more thing,” he said, taking her hand and putting the palm to his mouth.

Gaetana had gone bright scarlet. “What?” she got out.

“For God’s sake call me Giles; I cannot abide the damned title.”

“Sí. Giles,” she said happily. “What is it?” she added in alarm, as his face contorted.

“Nothing. Oh, dammit!” said his Lordship, searching for his handkerchief.

Gaetana got up. “Come and take my hand, and we shall go out: there is a door just here.”

He bit his lip but stood up and allowed her to lead him out.

In the little passage where Ned Jubb had knocked down Slingsby he held her very hard and wept into her shoulder. Gaetana simply put her arms right round him and held him as tightly as she could. After that he kissed her very thoroughly, discovering to his amusement, and greatly to his pleasure, that no-one had ever kissed her “like that” before. By this time, of course, he had become very cheerful, and positively masterful, indeed.

Gaetana was not deceived, however. She knew that she had found out for herself what her mamma had meant when she had said, nearly a year ago now, that rainy day in Brussels, that under their brave, important fronts, running their politics and their wars like the lords of creation, men were only silly boys at heart. Who only wanted love and forgiveness.

The strange thing was, Gaetana would speedily discover, that he was still a large, capable gentleman in whose company she still sometimes felt as small and inadequate and overawed, indeed shy, as she ever had. Sometimes she felt both these diametrically opposed things about him at once, even!

When she reported this some little time later to her mamma, Marinela just laughed and said: “Sí, sí, of course!”

It might have been said, in the case of Miss Ainsley and the Marquis of Rockingham—and Gaetana, blushing very much, was to confess as much to Hildy— that simple feeling had carried the day over correct moral principles. For she was still the daughter of a spy.

Hildy merely replied: “Oh, pooh! And do not mention Elinor Dashwood to me again, she is the most boring prude in literature!”

“Hildy, there—there was a moral principle at stake,” she said in a trembling voice.

“Rubbish; I remember quite clearly that on your return from the visit to the stupid Royal Mint you were overcome by having been given the marchioness treatment. And you realized he was a great lord, with a great position in society. Well, what creates respect for great lords? Moral principles? Rubbish: nothing but the stupidest forms of social intercourse! He has shown you that in the stupid world of the people to whom such things matter, your family is as acceptable as he! I think it was very well done of him. –And only think, when we dubbed him the Marquis of Carabas,” she added pleasedly, “that we had no notion of the depths of his cunning! To write off letters to Don Pedro and your Papa, and to persuade Lord Wellington to exert his influence with the Prince Regent—not to mention inviting both Wellington and York to his house to meet your family—!”

“Positively Machiavellian,” agreed Gaetana, frowning.

Hildy looked at her anxiously.

“I have taxed him with that, and he admits it was Machiavellian and—and I still love him!” said Gaetana, giving in and laughing. “Oh, Hildy, querida, what a very low sort of person I am!”

“Pooh!” said Hildy sturdily. “Making two persons desperately unhappy for the rest of their lives is what would have been the immoral thing!”

In that, Gaetana had to admit she had a point.

So feeling carried the day in spite of all fears to the contrary, and in the end, it might be noted, the two mothers had not had to intervene with words of wisdom after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment