25

Convalescence

As Rockingham made his way along the upstairs passage a maid was just coming out of Hildy’s room carrying an armful of flowers. He frowned, and the girl bobbed, gasping: “My Lord, they was all wilted!”

“Uh—dare say. Does that leave her with no flowers in the room, then?”

“Oh, no, your Lordship, there’s still lots left! All her visitors bring her flowers, my Lord!”

“Good,” he said on a lame note. He continued along the corridor, the frown not abating.

“Lionel tells me you are thinking of leaving,” he said, walking in on his aunt without ceremony as she was dressing for dinner.

“Yes. –Thank you, Gates,” she said calmly.

Gates bobbed, and withdrew.

“Really, Giles!”

“What?” he said in a bored voice, wandering over to the dressing table.

“Leave that!” she said sharply.

Rockingham put down the flask of scent, wrinkling his nose. “Don’t care for this.”

“No-one asked you to. Why have you burst in upon me like this, Giles?’

“Are you serious about leaving us?”

“Yes, and if you intend asking me to take Carolyn with me, I can merely repeat what I said to you earlier in the year: the sorts of visits we propose would be entirely unsuited to a young girl scarcely out.”

“Fast set you must move in, Lavinia,” he drawled.

“Nothing of the sort! They are largely political acquaintances, and—”

“Political and York, isn’t it?” he drawled

Lady Lavinia replied with measured disapproval: “Lionel accepted for us. And one can scarcely refuse a Royal Duke, however much one may wish to.”

“No, well, not if one is unable to think on one’s feet,” he drawled.

“That is quite enough! Have you burst in on me like this merely to be insulting?”

“Stop fussing, Lavinia, that wrapper thing is perfectly respectable. No, um, wanted to say, will little Miss Hildy be all right with only Dezzie to keep an eye on her?”

Lady Lavinia stared. “Naturally I would not contemplate leaving if I thought there was the least danger.”

The Marquis shuffled his feet. “I’ll have Mitchell in tomorrow.”

“You may do so, but he will say exactly what he said yesterday: the child needs rest; that woman—” She broke off. “Well, anyone may contract a fever!” she said quickly.

Rockingham replied, frowning: “She looks so thin and pale.”

“She has that constitution. Her mother assures me she has always been healthy, however, and Dr Mitchell confirms that there is no chronic weakness. However, I will stay if you wish it, Giles.”

“No—um—well, after all, her own family is just over the way, and Dezzie is used to sickbeds.”

“Exactly. She needs to be kept quiet and warm, that is all.”

“Mitchell advised against sending her home, though.”

“There has been a very nasty wind for the last two days,” said Lady Lavinia with heavy patience. “And the child has not been eating as well as— Well, as I said, I will stay if you wish it.”

“No. Leave Susan,” he said abruptly.

“I beg your pardon?”

The Marquis swallowed. “Leave Susan, Lavinia. She has a head on her shoulders and—well, when Dezzie’s out of the house it makes me damned anxious. Came home other day to learn she had gone out for a walk leaving the child with no-one in the house but those slips of girls!”

“Very well, I shall leave Susan. She will be glad of it, I dare say: she does not care for the Cowards, or the— And may I add, that if you were that anxious, you should not have left the house yourself.”

“I never thought she would just walk out!” he cried.

“No, well, all little Miss Hildegarde needs is rest and quiet. There was no danger.”—Rockingham looked unconvinced.—“Very well, Giles, Susan will stay.”

“I suppose I may not see you again until Christmas, then?” he said.

“Will you not be in town, later?”

He shrugged.

“We may perhaps collect Susan ourselves, in that case.”

Rockingham nodded. “Good. Drop me a line. And thanks, Lavinia.”

“There is nothing to thank me for,” she said colourlessly.

Suddenly he smiled and bent to kiss her large cheek. “Rubbish. You have been a positive rock. Mamma writes I should have sent for you the minute damned Eunice Heather started sneezing, you know!”

She looked at him ironically but not without affection. “So I have always maintained. Well, run along, if I am to finish dressing.”

Rockingham went back downstairs and, finding his Cousin Susan ready dressed and alone in the little withdrawing-room, informed her with his usual complete want of tact that he was to have the pleasure of her company for a while longer. And if she could think of a way to keep Julian’s brats quiet and amused during these nasty windy, damp days they were having, he, personally, would persuade Lady Lavinia to allow her never to go near the pianoforte again.

That night, as usual, he peeked into Hildy’s room before he retired. Tonight she was awake, just lying there still, with her hands outside the covers. Dezzie was sitting quietly by the bedside, reading. Rockingham trod over silently to her chair, and gripped her shoulder. “Should she not be asleep?” he murmured.

“No,” said Dezzie calmly: “she slept this afternoon and earlier this evening. She’s had a glass of milk and a piece of bread and butter. I recall I was the same when I had the influenzas: much brighter around this hour and then again at mid-morning.”

“Yes,” said Hildy in her weak little voice, but smiling at the Marquis. “How are you, sir?”

“Say, rather, how are you?” He came over to the bed and felt her pulse, frowning.

“I think it’s normal,” she ventured.

“Mm. A piece of bread and butter is not much.”

“I’m not very hungry,” responded Hildy simply.

“She’s all right, Giles. Leave her alone,” said Dezzie mildly. “A fever takes the appetite away.”

He responded calmly: “Go away, Dezzie; I wish to speak to Miss Hildegarde alone.”

Dezzie evinced neither surprize nor shock at this request. She got up and, saying: “I shall only be few minutes, Hildy. And Giles, try to remember she is an invalid, and avoid your usual bullying style,” went out.

The Marquis sat down in her chair and took Hildy’s hand. “Do I bully?”

“No,” said Hildy shyly, but smiling at him. “You merely have an abrupt manner, sir.”

“Glad to hear it.”

There was little pause. Hildy looked at him shyly, but not as if, he was glad to see, she was afraid of him. After a few moments she said: “I think you have looked in on me in the evenings before.”

“Yes. You were usually asleep, or nearly so.”

“Yes. Sometimes I was too tired to speak, but I knew you were there.”

Rockingham hesitated. Then he said with an effort: “Most of your family have been to see you.”

“Yes.”

His hand tightened unconsciously on her little one. “Gaetana has not been,” he said harshly.

“No,” she whispered, her eyes filling involuntarily.

“She is keeping away because of me.”

“I know,” whispered Hildy. “If there was anything I could do, I would.”

After a moment’s shock he said: “To—to bring us together? Is that what you mean?”

“Yes,” she said faintly.

“I thought— Has she told you why she will give me no encouragement?”

“Yes: Uncle Harry. It’s silly. But she sees it as a point of honour,”

“Yes,” he said grimly.

“She greatly admires the Cid. And Célimene,” said the faint little voice.

“Eh?” He would have expected Miss Ainsley to know the legend of El Cid; but Miss Hildegarde’s reference to Célimene suggested that she was acquainted with the works of M. Corneille!

“But I think they were a pair of sillies,” she added.

The Marquis swallowed. “I see. Yes, so do I, Hildy. –May I just call you Hildy?”

The frail little hand squeezed his. “Yes.”

Rockingham bit his lip. “If you desire to see her, I will go and fetch her.”

After a moment she said: “I do miss her.”

“I’ll fetch her, then.”

“No, it would upset her,” she whispered. “She has been so very unhappy.”

Rockingham went very red. “Has she?” he said hoarsely.

“Yes. And truly she only smiled upon Sir Noël Amory and those silly boys like Mr Edward Claveringham because she thought it would you give you a disgust of her, sir.”

“I see.”

“She has told Sir Noël she cannot encourage him to hope,” she whispered, her pale cheeks flushing.

“Has she, by gad?”

“Yes.”

He saw she was looking very tired. “Lie back.” He hesitated, then demanded abruptly: “Did you encourage those silly boys and Sir Ned for the same stupid sort of reason?”

Hildy’s eyes filled with tears “No. If you mean Sir Julian?”—He nodded.—“No. I did not know how I felt and—and Gaetana said that you said I mustn’t let him think I cared unless I truly did,” she said in the thread of a voice.

“Cursed fool that I was!” he said bitterly. “Oh, Lord, I’m sorry, little one!” he said as she gasped, and he realized he was crushing her hand.

“It’s all right,” said Hildy faintly. “I did hope Sir Julian would forget me. Only then I met Sir Ned and—and…” A tear trickled down her cheek.

“By God, the fellow shall marry you, if he so much as laid a hand on you!” he choked.

“Don’t be silly,” she murmured with a faint smile. “Fustian.”

“What?” he said numbly, bending over the bed.

“I said... fustian,” she said weakly. “Sorry.” She lay there with her eyes shut.

Scowling, the Marquis realized she had exhausted her strength. “Well, I will not fetch Gaetana if you do not wish it,” he said heavily.

Hildy’s lips moved in a “No.”

“I’d better go. I’ll fetch Dezzie again. Try not to think of Sir Ned,” he said stiffly. “Twenty and fifty-five don’t mix, y’know. Good-night, Hildy.” He laid her hand gently on her coverlet and went out.

Tears trickled very slowly down Hildy’s cheeks. She was aware that she could not have said if she was weeping for herself, for Sir Ned, for the Marquis, or Gaetana. Or, indeed, for Sir Julian, or Hilary Parkinson, or even Sir Noël. They were all sadly present in her mind, like mourning ghosts.

“I dare say the news is better,” said Mrs Urqhart on a dry note. “All the more reason why you had best not visit.”

Sir Ned flushed. “I was merely intending to leave flowers.”

“Well, if your informant was right, and seeing as how it were that cat Mrs Purdue what is better nor a town-crier, I’d give you evens she was, you was merely intending to get a sight of Hildy downstairs in a shawl a-sittin’ by the fire.”

“Mrs Purdue was merely repeating what Miss Girardon herself had told her,” he said in an annoyed tone.

“Ned, you is not deceiving me, you know. In fact I would advise you not to waste your breath.”

“No,” he sighed, walking away to the window and staring out unseeingly at the gardens.

“You’ll make it worse for the girl, as well as for yourself, if you persist,” she said in a not unkindly tone.

“Aye. I’ll go back to London,” he said abruptly.

“Not before tomorrow night, you will not!” she returned smartly.

“Betsy,” he said with a sigh: “I shall be the death’s head at this feast you have planned.”

“Aye, but you can be a death’s head what is balancín’ my numbers!” she said strongly.

He sighed. “Who is to be there?”

Mrs Urqhart glared.

“No—besides Lady C.,” he said, lips twitching.

“Oh!” she said, mollified. “—I am not askin’ you to make a play for her, you know, at this stage,” she added kindly.

Ned made a wry face. “I doubt I shall have to. Though you are right: I never felt less like— Well, never mind. Who else?”

Mrs Urqhart thought that Ned could flirt with Lady Desdemona in order to turn Lady Charleson green as grass and hot up her pursuit of him. Presumably this explained why the other gentlemen present would be, apart from Mr O’Flynn, of course, only the house guests of The Towers, all of whom were well on the sunny side of thirty-five.

“Oh, yes: that will work out splendidly!” he said. “I shall conduct an à suivi flirtation with Lady Desdemona, Mr O’Flynn and yourself will indulge in genteel conversation, Lord Lucas may bore my poor Jo to death by telling her what an admirable character is Mrs O’Flynn’s, Charles Grey will be delighted to be entertained with tales of ’licious Daffa-Down-Dilly and ickle p’etty Tweetie, and Noël and Lady C. will be free to flirt to their heart’s content!”

“All right, it was a mistake!” she shouted.

Ned said nothing,

“Oh, get along with you, I’ll come over to the Place with you meself if you’re that set on goin’!” she said, struggling to her feet.

Ned got up and put a hand under her elbow. “Are you sure, Betsy, my dear?”

“Aye. Acos we has only the one life, me deary. And if you wishes to see little Hildy once more, then why not?”

He bit his lip. “You are right in saying it may upset her.”

“And I’m right in sayin’ that at thirty she’ll look back and wonder what she ever was at, too!” she said strongly.

Ned’s lips twitched. He dropped a kiss on her cheek. “If she remembers at all.”

The report which Mrs Purdue had extracted from Carolyn and subsequently conveyed to Ned Jubb had been perfectly correct, and Hildy had now spent two afternoons downstairs. The weather was still chilly and very windy, so Dezzie had cheerfully vetoed her going home just yet. Hildy had been too weak to argue.

Very naturally, the ladies of the house had not left their recuperating invalid alone with Sir Julian Naseby. Had he thought clearly about it Julian would of course have realized that this would be so. He had found himself very dashed, after days of worrying about her followed by days of hoping she would be well enough to come downstairs, to discover that when she at last did so a tête-à-tête would not be possible.

On Hildy’s first coming down, Julian had of course bowed over her hand and expressed his delight at seeing her downstairs. Since Ermy and Tabby at that precise moment were jumping and crying “Huzza!” this had possibly not made terribly much impression on her. He was filled with a gloomy feeling that she must think him a pretty poor sort of fellow, but could not figure out a way in which to explain that he had avoided the sickroom not out of fear of infection, but out of a regard for the proprieties. What with not being able to get near her privately in addition to these brooding thoughts constantly running through his mind, Julian was not in the best of spirits. And in spite of his excellent manners, this fact was apparent to more than one of the house party.

Lady Desdemona, in fact, remarked three times to her brother that his friend was dashed blue-devilled and what was the matter with the fellow, the third time adding the casual enquiry, was it that he was entirely lacking in backbone or merely that he was a jellyfish? These alternatives did not go down at all well with the Marquis, in fact they caused him to bellow: “Get out of my study!”

“Thought we were going to ride out over Upper Daynesfold way today?” said his sister, unmoved.

“I have changed my mind.”

“I’ll go by myself, then,” said Dezzie cheerfully, going out.

The Marquis glared at the closed door. After a few moments Mr Wetherby, who had been present throughout, gave a discreet cough.

“Where were we?” said his employer, groaning.

“Er—we could leave these accounts until tomorrow, sir.”

“Rubbish. Get on with it,” he said shortly.

Mr Wetherby got on with it.

Having finished his business, however, Rockingham went in quest of Julian. He found Hildy, Anna, Rommie and Ermy in the little sitting-room, Hildy on a sofa with her feet up and a warm shawl over her, Anna sewing quietly in a chair by her side, and Rommie and Ermy, both reading, seated on the rug with their backs propped against Hildy’s sofa.

The Marquis did not remark on this casual scene in his sitting-room, he merely said: “Where the Devil’s Julian?”

“Didn’t he say something about the conservatory, Anna?” recollected Rommie.

“Yes, but I don’t think... Well, he may have meant to go in there.”

Rockingham sniffed. “Mm.” He came over to the head of her sofa and looked over Hildy’s shoulder. “What are you reading?”

She touched the book in her lap. “I am not reading at all, sir. I did think I might, but...”

“Pope?” he recognised with a smile. “I think that volume belonged to my great-grandfather! Do you not find him too dry for a lady’s taste?”

“It says ‘Henry Hammond’ on the flyleaf,” said Hildy.

“Grandpapa as a young man, then,” he said. “Well?”

“Yes, I find him much too dry for a lady’s taste,” she said dulcetly.

He laughed, and squeezed her shoulder. “Aye! Have you read much of him? Which do you like best?”

“I must confess, although I admire the Essay on Man, my favourite is The Rape of the Lock,” she said with a twinkle.

“Aye, it is mine, too! I recall Grandpapa was used to admire The Dunciad very much, and laugh over it, you know, but of course he knew all the personalities. To our generation it has certainly lost its savour, I find.”

“Yes, I cannot read it at all,” confessed Hildy. “Your Grandpapa must have lived to a good old age, then, sir, if he was a young man in Pope’s day?”

“Mm? Oh—yes, he was in his eighties when he died. Just as well,” he said, making a face: “it meant that Papa did not have much time to do his best to drive the property to rack and ruin.”

“Did he?” asked Ermy with interest, looking up from her book.

“Little pitchers,” replied the Marquis with a grimace.

“Well, of course!” said Hildy, laughing a little.

“Did he, Uncle Giles?” persisted Ermy.

“Yes, Ermy, he did his best, but thanks to a combination of a restive horse, too much brandy, and a farm gate, Providence was able to intervene before he’d towed the family into the River Tick,” he returned on a grim note.

“At least you are not patronising her,” noted Hildy.

The Marquis looked at Ermy ironically. “If she’s old enough to ask, she’s old enough to take the answer.”

“Yes,” agreed Ermy, nodding. “My grandpapa was a most admirable man,” she informed them.

“So he was, poor Ludo,” said the Marquis with a sigh.

“Great-Aunt Mary says Papa is not half the man that he was,” added Ermy on a doubtful note.

“Ermy!” cried Rommie indignantly, turning very red.

“Well, she does.”

“Yes, and she also says that Mamma was mad!” cried Rommie angrily, tears starting to her eyes.

“Your Great-Aunt Mary is a stupid and prejudiced old woman,” noted the Marquis in a blighting tone.

Anna turned positively puce, but the two little Naseby girls looked up at him eagerly.

“Yes, she is!” cried Rommie.

“Yes, she is,” agreed Ermy in a relieved tone. “I never believe anything she says, actually,” she informed the company.

“Aye, well, keep it that way,” recommended Rockingham.

“I believe Sir Ludovic was generally much admired for his charitable work,” said Hildy, somewhat feebly.

Rockingham pressed her shoulder again. “Aye. Not to mention his charitable heart,” he noted drily.

Hildy twisted her head to look up at him uncertainly.

“Well, ain’t that the important thing?” he said with a wry twist of the lips.

“Well, yes. For the works spring from the heart’s motives. But you are quite right, it is of course the point that in general is not mentioned.”

“Not in polite society, at all events. –Well, so you don’t feel much like reading this afternoon, not even Mr Pope?”

“Um—no. I lack the energy,” she admitted. “It is very pleasant, just sitting here and looking out at the gardens.”

“I did offer to read it aloud for her, Uncle Giles,” said Rommie on an anxious note.

The Marquis winced. “Very kind. Well, if Julian may or may not have gone to the conservatory I don’t think I shall bother pursuing him. Would you care for me to read to you, Miss Hildy?”

Hildy pinkened and smiled up at him shyly. “That would be lovely, sir.”

“He does read quite well,” allowed Ermy. “But Rommie does the voices much better.”

“There are no voices to speak of in Mr Pope,” noted the Marquis, coming round to pick the book up off Hildy’s lap.

“Just as well,” said Ermy calmly.

“There are lots of rhymes, though,” noted Rommie.

“Quite. The trick is,” said the Marquis in a super-kind voice: “not to read ’em in a sing-song.”

Hildy, who had been watching and listening in some amusement, at this bit her lip. Anna had been looking plainly distressed: she gave a little gasp.

But Rommie replied calmly: “I know, only somehow when it comes to the point, I can’t stop myself.”

At this Hildy gave a little laugh and said: “I perceive that when Rommie and Ermy and Tabby come to visit, there must usually be an amount of reading aloud done, Marquis!”

“Well, yes,” he said, grinning. “At Christmas in particular, if the ground’s too wet or too hard for hunting, there is not that much else to do, cooped up in the house.”

Hildy smiled at him with considerable affection. “No, indeed.”

“We sometimes play charades, only Uncle Giles doesn’t always care to,” said Ermy. “Sit here, Uncle Giles,” she added, squeezing up a little and patting the rug hospitably.

“Er—no. Thank you all the same, Ermy, but there comes a time in a man’s life,” said the Marquis, pulling up a chair, “when he realizes his legs don’t take too kindly to sitting on the floor any more.”

There was a puzzled silence, during which the Miss Nasebys looked hard at the Marquis’s legs and Anna very evidently tried not to. Finally Ermy said: “When he gets the gout, do you mean, Uncle Giles?”

“No!” he choked.

“No,” said Anna faintly, very red.

“Mr Jerningham has the gout,” she noted.

“Ye-es... But he’s much older than Uncle Giles,” Rommie pointed out. “Which is odd, because if Lord Welling should die, he will be the heir.”

“Yes,” agreed Ermy, staring at the Marquis’s legs. “They look all right.”

Rockingham took a deep breath.

“I think he just means when their legs grow!” hissed Rommie in what might have been meant to be an undertone.

“Oh,” said Ermy blankly, staring at the Marquis’s legs again. Or still.

“No,” said Hildy in a strangled voice. “It is when their legs have grown and their hair starts to grey and their joints to stiffen, but before the gout is actually upon them!”

Anna gave a horrified gasp but the Marquis, grinning, merely said: “Very true. Shall I start?”

“Yes, please,” agreed Hildy. “—No, wait!”

Rockingham had opened his mouth. He shut it again, looking surprized.

“It is about a lady who had a lock of hair stolen from her: snipped off, you know,” said Hildy composedly to the Misses Naseby.

“I see!” cried Rommie. “Not like the rape of the Sabine women?”

“Not in the least,” said Hildy composedly.

Looking disappointed, Rommie, said: “No. Well, go on, Uncle Giles.”

The Marquis took a breath. “‘What dire offence from amorous causes springs...’”

When Julian looked in with a bunch of flowers from the conservatory, they were still hard at it.

“Sit down, Papa!” hissed Rommie.

Julian sat down meekly, clutching his flowers.

“‘...This Lock, the Muse shall consecrate to fame, And midst the stars inscribe Belinda’s name,’” finished Rockingham, at what at least two of those present considered to be long last.

Hildy, all smiles, clapped her hands. “That was splendid!”

“Don’t thank me, thank Mr Pope,” said the Marquis with a grin.

“Stop fishing: you know you read it very well!” she said with a laugh.

“Yes, indeed, Uncle Giles,” agreed Anna valiantly.

“If a silly man tried to cut off one of my curls, I would give him a wisty castor, I can tell you!” cried Ermy fiercely.

“Eh?” croaked her father.

“Boxing cant, Julian: can’t imagine where she picks it up,” said his friend severely.

Hildy gave a smothered giggle.

“Well, it ain’t from me, I can tell you!” returned Sir Julian heatedly.

At this Hildy laughed aloud.

“Well, it ain’t,” he said in an injured voice. “Mamma don’t allow it, and what is more, nor do I,” he added, looking severely at the culprit,

“Silly! He meant himself!” cried Hildy.

“Aye, I did. Slow, ain’t he?” noted the Marquis.

Julian gave a forced smile.

“So you enjoyed it, did you, Ermy?” said Hildy quickly.

“Yes. Only I don’t see why the lock had to go up to Heaven,” she replied seriously.

“It was a joke, silly!” cried Rommie.

“Yes. –Don’t call her silly, it is not every child of ten who would be capable of even listening to Pope,” said Hildy.

“She is nearly eleven,” noted Rommie, scowling.

“Yes, well, many persons of well over twenty in fact would not listen to Mr Pope with attention and enjoyment,” said Hildy, smiling at both of them and very much not looking at either Anna or Sir Julian. “You are right in that it is very largely a joke, Rommie: the whole thing is written in an exaggerated style as a joke, of course.”

“What about the peroration?” said Rockingham drily.

“‘So long lives this and this gives life to thee’?” replied Hildy, laughing. “I do not deny that Mr Pope had a good opinion of his own abilities, sir!”

“It didn’t say that,” said Rommie in confusion.

“No. Well, not that I noticed,” agreed her father cautiously.

“No,” agreed Ermy.

Hildy bit her lip and looked uncertainly at Rockingham.

“Well, go on; you have started: you had best explain.”

“I have not the strength,” she said, lying back on her cushions.

Anna started forward anxiously but her uncle said drily: “Sit back, girl. She is joking.”

“Not altogether,” admitted Hildy, opening her eyes and smiling at Anna.

“Aye, well, I don’t guarantee I have the strength to explain it to Julian,” agreed Rockingham. “But I dare say I can explain well enough for Rommie and Ermy. You see, girls—”

“I see!” concluded Rommie with a laugh.

Julian scratched his head. “Yes. But mind you, I think Miss Hildegarde’s in the right of it and the fellow has a dashed high opinion of himself.”

“The two are not incompatible,” said Hildy, twinkling at him.

“Ooh, no. Ooh, that makes it better!” cried Rommie, hugging her knees and beaming up at her.

“Well, I’m glad you can see it,” said her father. “Can’t say I can. –The girls have got all the brains of the family, y’know,” he said to Hildy. “Inherited ’em from Papa and their mother. Well, and Mamma, of course, she’s a dashed intelligent woman. Reads as much as you do, I dare say.”

Hildy looked at him cautiously. “Your sister Mrs Horsham is a great reader, too.”

Julian sighed. “Aye. It’s not that I dislike poetry. Only I must say I prefer shorter pieces. Some of those little songs of Rommie’s, now: they’re pretty.”

“‘My love is like a red, red rose,’” agreed Rommie, nodding. “Papa, that reminds me, are not those flowers for Hildy?”

“Yes, said Julian, blushing. “Well, of course you may thank Giles, it is his conservatory I have robbed!” he added, rallying.

Hildy also blushed in spite of herself. “Thank you, Sir Julian,” she said as he laid the flowers gently in her lap. “—I confess I find some of Burns so very Scotch that I cannot understand him. Christabel has a small volume of him,” she explained. “And even those I do like very much, such as Robert Bruce’s March to Bannockburn, although I can read them happily in my head, when it comes to speaking them aloud I am quite lost.”

“Mm—dialect,” agreed Rockingham. “Do you not have a volume of your own, Hildy?”

Julian here went even redder, gritted his teeth, and glared at the carpet. Perhaps alone of the household, he had not realized that Rockingham, though he did try not to do it in company, had fallen into the habit of addressing Miss Hildegarde by her pet name.

“No: I do not own many books,” replied Hildy simply. “Dr Rogers left me a few of his favourites, however.”

“I see.” He got up and went out.

“Is he cross?” said Ermy uncertainly.

“No, silly!” cried Rommie, laughing. “He will have gone to find Hildy a volume of Burns!”

“Yes,” said her father in a stifled voice.

“Oh, good, now that I’ve started thinking about him I should like to re-read him,” said Hildy pleasedly.

“Yes, but—” Julian broke off, biting his lip.

“What?” she said in bewilderment.

“Nothing,” he muttered. “Uh—dashed intelligent fellow, of course, old Giles. Well-read, too.”

“So I am discovering,” agreed Hildy, smiling at him “And I have heard something of his charitable work over the past few months. I can see why you so like and admire him, Sir Julian.”

“Yes,” he said with a sigh. “Admirable chap. Takes his seat in the House, too, y’know.”

“Yes, I think you once told me that, sir,” she agreed.

“Did I? Aye,” he muttered, flushing.

“The Anne Girardon Home is one of his, Hildy, did you know that?” said Ermy.

“Yes, I had heard that, Ermy.”

“Grandmamma wished to name Papa’s homes for girls the Sir Ludovic Naseby Memorial Homes, only Papa thought Grandpapa would not have cared for it,” she continued happily.

Hildy looked numbly at Sir Julian.

“Not ‘Homes’, idiot: ‘Foundation!’” cried Rommie scornfully.

“Yes—er—don’t go on at her like that, Rommie,” he said uncomfortably. “The Foundation runs the homes, y’know, it’s more or less the same thing. –Well, Papa would not have cared for it: didn’t care to splash his name around the place,” he said to Hildy, flushing. “Mamma forgets. Misses him, you know, but she doesn’t always remember accurately.”

“We have often thought that must be true of Mamma’s recollections of our papa,” she agreed with an effort. “What—what have you called your foundation, then, sir?”

“Er—well, called it the Naseby Foundation, in the end,” he admitted. “Compromise, you know?”

“Yes, of course!” cried Anna eagerly. “It would have made your mamma happy, without—without misrepresenting your dear papa’s memory!”

“Yes, that’s it,” he said gratefully. “Um—dare say you may not approve of compromise, Miss Hildegarde,” he added awkwardly. “But—um—well, there you are. Like Miss Hobbs says.” Hildy opened her mouth to assure him she was not that rigid in her ideas and that in a case like this she most certainly did approve of compromise, but at that moment the Marquis returned. He dropped a small volume into her lap and before she could utter, said: “Keep it.”

Hildy picked it up slowly. “What?” she said faintly, staring at the handsome calf binding, emblazoned in gold with the Hammond crest.

“Keep it.”

She opened it numbly. Someone had scrawled across the flyleaf in very black ink (and a very young hand): “Giles Henry Bernard Jerningham Hammond. 1793.”

“Sir, this must be your own book,” she faltered.

“Mm? Yes. Keep it.”

Rommie got up and came to look over her shoulder. “1793? How old were you then, Uncle Giles?”

“I don’t know!” he said impatiently. “Old enough to read Burns, at all events. We had gone to visit distant relatives in Scotland, and Mamma and I found a bookshop in Edinburgh— Anyway, that is irrelevant. It is Miss Hildegarde’s book, now.”

“I—I couldn’t take it,” said Hildy faintly.

“Rubbish. I am giving it you.”

“It is very kind in you, sir, but will you not miss it?”

“No, I have another edition,” he said in an indifferent tone.

Hildy looked at him doubtfully. Quite possibly he did: the library at Daynesford Place must be extensive. But a volume that was a souvenir of a trip with his beloved mother...

“He does not generally say things he does not mean, Hildy: he really wishes for you to have it,” said Rommie.

“Then—then I accept,” she said weakly. “Thank you very much, Lord Rockingham.”

“It’s nothing. –Ring the bell, Rommie,” he ordered.

Rommie rang the bell obediently, not neglecting, however, to say: “Why, Uncle Giles? Ooh, is it time for tea?”

“No. Well, on second thoughts, possibly some of those who have sat obediently through The Rape of the Lock without uttering a peep, may deserve tea, yes. William,” he said as the footman who usually served the little sitting-room duly appeared: “should you say it was time for tea?”

William, unmoved, replied calmly: “Certainly, my Lord, if your Lordship should wish it.”

“Ain’t it wonderful?” remarked his Lordship to the company. “My consequence may move even the sun in his course.”—Hildy choked.—“Yes, tea and cakes, then, please, William, and see if Miss Tabby should wish to come down for ’em. And bring me pen and ink.”

William bowed. “Yes, my Lord. Should your Lordship wish for paper also?”

“No, I’ll inscribe my message midst the stars,” he noted.—Hildy and Rommie both gave strangled squeaks.—“No, no paper, thank you, William.”

As the footman bowed and exited, Rockingham took the Burns from Hildy and began flipping through it. “Here: this is a nice one,” he said. He sat down and began to read aloud: “‘Go fetch to me a pint o’ wine...’”

There was an awestruck silence when he’d finished. No-one even asked what a tassie was.

Finally Ermy ventured feebly: “I said he could not do voices.”

“How right you were,” said Hildy faintly.

“Meant to be Scotch, was it?” asked Julian kindly.

Hildy choked.

“It was a—a gallant effort, I suppose,” croaked Rommie.

“You had always liked this poem, hitherto,” he noted sourly.

“Yes. Pray do not read any more aloud, sir,” Hildy said feebly.

“Well, I’m like you: I can hear it in my head!” he said with a laugh, handing it back.

“Yes!” agreed Hildy, smiling at him.

Julian, who had thought his “Meant to be Scotch” remark had gone over rather well, watched glumly as the Marquis smiled back.

The tea had just been brought in, Miss Tabby had just been seated firmly by her papa, and the Marquis was just scrawling Miss Hildegarde’s name in his Burns, when William re-entered to announce callers.

The Miss Nasebys had not yet been privileged to meet Mrs Urqhart but they had heard a lot about her by this time—mainly from Lord Rockingham, so not all of it had been phrased in a manner which everyone would have said was fit for young ears—so of course they were immediately agog.

Mrs Urqhart came in beaming on Sir Edward Jubb’s arm. In honour of the cool, windy day she was wearing her sable wrap over a very blue woollen pelisse. Rommie and Anna, at least, were old enough to have learned from Lady Naseby and Grandmamma Hobbs that brown furs were never to be worn with blue, so their jaws dropped. The bonnet, scarlet watered silk with a very upstanding poke, much blue-and-white striped ribbon in a profusion of bows, and several very large and very blue ostrich feathers, could not but add to the general impression. So much so, indeed, that the twin ruby and gold bracelets over the tight lilac kid gloves went unremarked by any save Rockingham, who noted silently they were some of the most exquisite stones he had ever seen, as he showed his guest to a chair.

“Good, we is in time for a cup of tea, I see!” she said, puffing a bit and unfurling her fan.

“Allow me, ma’am,” he said gravely, taking it and fanning her gently.

“Lawks, I never did think to see the day I was fanned by a real live marquis!” she said with a chuckle.

Having been thanked and told that that was enough fanning, and he had best sit down and drink up his tea before it went cold, his Lordship returned meekly to his seat.

Conversation thereupon became general. Though eventually Tabby did say abruptly: “Have you seen a snake?” and was shushed by her father.

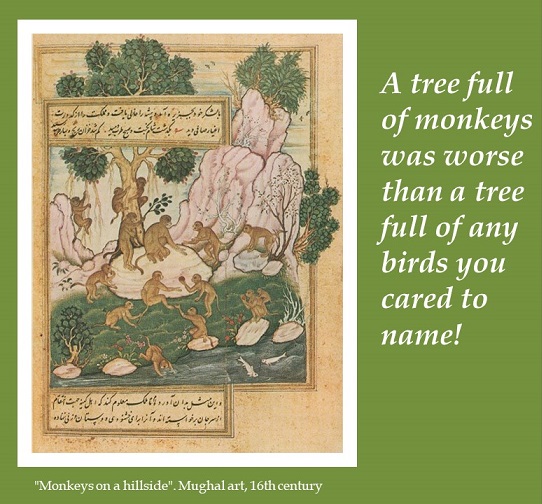

Mrs Urqhart, however, promptly invited Miss Tabitha onto her capacious lap and, once she had been brought to an appropriate recognition that Tabitha was nearly seven and therefore not a baby, was allowed to put an arm round her and regale her with pieces of cake and tales of snakes and their charmers, and elephants, camels, peacocks and monkeys. Tabby did not appear to be having any preconceived notions overset—perhaps she had not, at nearly seven, very many of them—but Sir Julian, Rommie and Anna all looked a trifle stunned to learn that elephants was very mild and friendly creatures, camels could spit a half mile and had a vicious look in their eyes, aye, and would bite, too, the brutes, peacocks was raucous birds with not that much flesh on ’em and not near so tasty as a pheasant, though she would grant you the feathers was pretty—here the Marquis’s eye inadvertently met Hildy’s and she smiled warmly at him, whereat both Sir Ned and Sir Julian looked fit to murder him—and monkeys was dirty, mischievous, thieving little brutes, and shriek! My, did they shriek! A tree full of monkeys was worse than a tree full of any birds you cared to name!

After which she declared that that was enough about the Indian animals for the nonce, but that Tabby and her sisters must come to visit very soon. The Naseby children all nodded fiercely and looked pleadingly at their papa.

“It’s very kind in you, ma’am, but they’ll be dashed nuisances, you know.”

“I will not be a ’oosance!” cried Miss Tabby loudly.

“Lor’, no, out o’ course you won’t!” declared Mrs Urqhart, bussing her cheek heartily. Her relatives looked at her uneasily: Tabby did not normally care for gratuitous embraces; but she appeared unmoved.

“Then I accept for them, ma’am, with many thanks,” said Julian with his pleasant smile.

“I shall enjoy it as much as they does, bless ’em! Here, is they allowed to eat sweetmeats?”

“Yes! Like Hildy’s!” cried Ermy, forgetting herself.

“Pink, pink!” cried Tabby, jigging on Mrs Urqhart’s knee.

“Liked the pink ’uns, did you? They be just like the white, only coloured up some with this red stuff as she uses. Yes, my lamb, you shall have pink ’uns.”

“Huzza!” cried Tabby.

“I—I haven’t been feeling very much like eating,” murmured Hildy, blushing a little, “so of course the children helped me with the sweetmeats. It was such a lovely box, Mrs Urqhart: thank you so much.”

“Well, me dear, it was Bapsee as did the work and Ned as got up the energy to get dressed up and drive over here with ’em,” she said with a rueful smile. “Only I’m very glad to hear you liked ’em. –You ain’t eating much now, either,” she noted.

Hildy blushed again. “I have still not recovered my appetite,” she murmured.

“Try this cake, here,” suggested Rockingham, getting up with a plate.

“No—really, sir, I could not.”

“We have tired you out,” he said, frowning. “Too much Pope.”

“Too much Scotch, you mean!” said Julian on a rude note.

“No—it is just that I am not very hungry,” said Hildy.

Everyone could perceive she was now looking very tired, however.

“Drink up that tea, and then you may go back to your bed,” said Rockingham, scowling.

Obediently Hildy raised her teacup, though her hand shook a little.

“She has had it for today, me Lord,” said Mrs Urqhart in a low voice.

“Yes. We have been reading poetry and—and talking, and so forth... I’m afraid I let it go on too long.”

“She was up much longer yesterday, Uncle Giles!” urged Rommie.

“Yes, but we were just sitting quietly,” said Anna on an anxious note. “Hildy, if you cannot manage that tea—”

Hildy put her cup down thankfully. “It’s silly,” she said in a tiny voice, leaning her head back against cushions.

Rockingham got up. “Come along—back to bed!”

“I can’t,” she whispered.

“No, I can see you can’t,” he said in a cross voice.

The company watched silently as Lord Rockingham scooped Miss Hildegarde up in his arms as if she had weighed as little as one of her cushions.

“Uncle Giles will put you to bed, Hildy,” explained Tabby helpfully.

“Come along, Anna, open the door!” he said irritably.

Anna gasped, and bounced up before either of the other two gentlemen present could move, and ran to the door.

“Don’t be sick again, Hildy,” added Tabby anxiously.

“No. Just... tired,” said Hildy, very faintly.

“She is too tired to talk, Tabby, but she is not sick,” said Rockingham firmly, bearing his fair burden out. “Come along, girl, or do you imagine I intend undressing Miss Hildy myself?” he added to his niece.

Gasping: “No! Of course not!” Anna followed them out.

The company looked dazedly at the closed door.

“Hildy is not sick again,” stated Miss Tabby.

Mrs Urqhart, as was to be expected, recovered herself first of the older persons present. “No, out of course she is not, deary! A fever does that, you know: tires you out, all of sudden, like. I dare swear she will be downstairs again tomorrow!”

“Yes, tomorrow. May we come to your house tomorrow?”

“Mind your manners, Miss,” said her father limply.

“Well, I don’t know as that would be the best day, me dear. We has a party planned for the evening and Bapsee will be too busy to make the sweetmeats for you. S’pose you come the day after, eh?”

“Yes. Day after.”

“Mrs Urqhart, are you sure it will not be too much of a bother?” said Sir Julian, endeavouring to pull himself together.

“Nay, it will cheer me up no end! Ned, here, has to go back to London that mornin’, you know, and my young gents is out all day shootin’ birds and I dunno what! So I shall be glad of the company. –Shall I not, Ned?” she added loudly.

Sir Edward jumped a foot. “What? Oh—yes, indeed, my dear,” he said lamely.

... “I never seen two fellows with their noses more thoroughly out of joint,” she said reflectively as they drove away.

“Bite your tongue,” replied Ned, biting his own lip.

“Why, he is worth ten o’ the pair of you! I never seen anything like it! Up he hops and scoops her up like a babe and is out of the room before you two great gabies can do more’n gape!”

“Damn it, Betsy, it was his house!”

Mrs Urqhart sniffed loudly.

“You are correct,” he admitted lamely. “He has a great deal of common sense.”

“For a marquis,” she noted sardonically.

“For a person of quality—quite,” said Ned Jubb, biting his lip again.

“You does not know whether to laugh or cry, or at the least, curse, does you? Well, you may do any, acos you can’t shock me, whichever. Only if I was you, I would laugh.”

Ned did laugh, if very sheepishly, as the vigorous old lady concluded on a pleased note: “Made monkeys of the both of you!”

No comments:

Post a Comment