15

The Nabob’s Widow

“Why, it is Miss Maddern!” cried Captain Lord Lucas Claveringham loudly. “What a piece of luck, Noël!”

Sir Noël Amory had already spotted that the slender figure up on the hill was Miss Ainsley, so he was not entirely surprized that the striking young woman in the sapphire blue was Miss Maddern. Though he was just a little surprized to see her dressed so, in this rural setting, the more so as Mrs Urqhart immediately said pleasedly: “Now, that is something like a pelisse! I cannot be doing with these dowdy little mimsy-pimsy get-ups the girls wear these days, and so I tell you frankly! Noël: is she yours, my dear boy?”

“No, dear Aunt Betsy,” replied Sir Noël with a laugh, “she is very much not mine! I fancy Lucas, here, would not mind if she were his, however!”

“A fine figure of a woman,” said Mrs Urqhart, nodding approvingly. “I declare, she puts me in mind of myself at her age! Now that,” she added in what was scarcely an undertone, “is what I call a bosom!”

With his usual easy manners Sir Noël then led her over to Miss Maddern and Mr Ainsley and proceeded to effect introductions, Mrs Urqhart explaining quite gratuitously as he did so that she was not a true aunt at all, but the widow of Sir Noël’s late papa’s late cousin, and though she should not dream of inflicting herself on dear Noël in town or indeed at his home, because she hoped she knew what was what, and it would not do at all—though out in India Mr Urqhart had not given a fig for such stuff, she was very glad to say, even if her pa was an ironmonger and his father before him—she did so love to have him come and visit at her house with his friends!

At this Sir Noël gracefully kissed her raddled cheek and said gently: “You are being absurd, dear Aunt Betsy. Of course you are welcome at my home at any time.”

Betsy Urqhart produced a flag-like handkerchief and trumpeted into it, saying sadly: “Your mamma does not feel that, dear lad, and so we both know: there is no point in wrapping it up in clean linen!”

Hildegarde and Mr Charleson had come up during the introductions and Hildy at this said eagerly: “No, indeed, what is the point of hypocrisy when everyone knows the opposite to be true?”

“Exactly, my dear, and you had best give us a kiss, if you ain’t too ladylike for it!” said Mrs Urqhart with a jolly chuckle.

Hildy went pink and kissed her cheek shyly.

“My, as I live and breathe, you is the very spit of old Sir Vyvyan Ainsley, the wicked old reprobate as he was, too!” said Mrs Urqhart, staring into her face.

“Well, he was my mamma’s grandpapa, I suppose it is not impossible.”

“Heavens to Murgatroyd: you is never Patty Ainsley’s child?” she cried.

“Yes, and so is Christabel, here—she is the eldest; and Amabel, the lady over there in the yellow, and we have two brothers, and two more sisters at home!” said Hildy with a little laugh.

“Never! Don’t time fly! Why, it seems but yesterday that they brought Patty Ainsley out and we seen her all decked out in a white gown with green stripes and a big straw hat, and Pa, he says to me, ‘Now, if you was as elegant as that one, Betsy, I dare say we might manage to make a fine lady of you, only as it is, you had best go off to Brother Thomas in India and see if you can catch a young officer!’” said Mrs Urqhart with her unaffected laugh.

“And did you!” asked Hildy with unaffected interest, what time Christabel’s face took on a rigid look.

“Oh, lawks, yes, my deary! Well, my Pumps—we called him Pumps, that was a silty nickname, little Missy—my Pumps was naught but a sub-lieutenant, and not like to get his advancement, neither, for his papa could not afford to purchase it, so Uncle Thomas says: ‘You had best have him, Betsy, if it’s him you wants, and we’ll bring him into the business!’ So we done it, and Pumps never looked back, he took to it like a duck to water, never mind all his noble relations, and in the end Uncle Thomas Shillabeer left the entire business to him and me, not having chick nor child of his own!” She beamed at her.

“I see, so your uncle and husband were India merchants? How fascinating!” cried Hildy.

“Aye: and when me and my Pumps come home at last, there was never anything like it, we had canvas crowded on tops’ls and jibs and I dunno what, and flew home in a record time, and all the staff of the London office a-standing on the dock to cheer us when we arrived!”

“How exciting!” breathed Hildy.

“Indeed!” agreed Paul with his nice smile. “You have certainly seen life, Mrs Urqhart!”

“Aye, that I have, Mr Ainsley. Now, stay: if these young ladies be Miss Patty’s children, then—”

“Harry Ainsley is my papa,” said Paul with a twinkle in his dark eyes.

“Never say it! Young Harry Ainsley! He were only a lad when I left for India, my dear. Though I did hear as he got up to all sorts of mischief, a bit later.”

“Yes, including marrying a Spanish lady, who is my mamma; and he is now living in Spain with her.”

“Land save us! And does they have natives in Spain, Mr Ainsley?”

Paul replied without a tremor: “Not very black ones, no, Mrs Urqhart. They are not generally any darker than I.”

“Well, well, well! That’ll be where you gets those naughty black eyes o’ your’n from, eh?” she said with a rich chuckle, biffing him violently on the arm with her fan.

He staggered slightly but made a quick recover. “So you’ve noticed?” he said, giving her a melting look.

Mrs Urqhart gave a shriek. “Ain’t he a one? My, you reminds me of my Pumps in his prime, he had just such a look on him!”

Certain of those present could not but feel that this remark was no more than Mr Ainsley deserved.

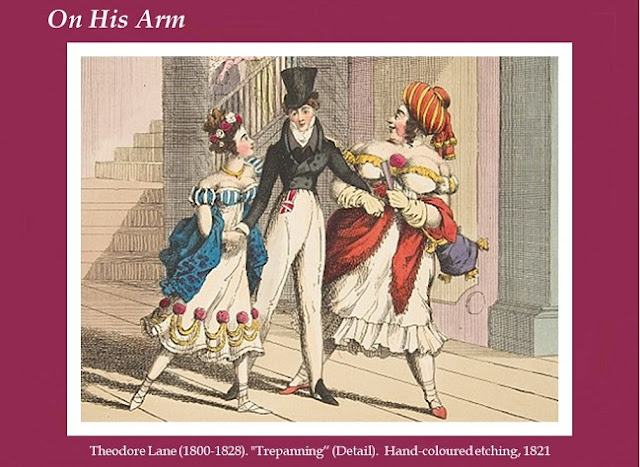

Sir Noël then led Mrs Urqhart over to Amabel’s group, and introduced her to them, and Paul introduced her to Miss Dewesbury and Mr Parkinson—though he did not let go of Miss Maddern’s arm. And she, he was very glad to note, made no effort to free herself, and responded to Captain Lord Lucas’s flattery with mere politeness.

Introductions over, Mrs Urqhart then biffed her nephew smartly on the arm with her fan (why she was carrying a fan in such cool weather was a mystery, though one or two persons present reflected that it was doubtless for the purpose of biffing young gentlemen on the arm) and said: “Well, you had best scoot up the hill and retrieve her, Noël!”

Grinning, Sir Noël bowed, kissed her hand, and went off up the hill to Gaetana.

“I dare say she won’t have him, never mind what that rich old uncle left him, acos the Amory lands weren’t what they was, by no means,” she said, shaking her head. “His pa was a fool, a gentleman he may have been, but a fool. My Pumps told him again and again, once you sell off land it’s gone for good, but would he listen? No, he would not! So now they’re left with the house and its grounds and a couple of farms: and him with his sisters and his ma to provide for! And she may be a very fine lady, and I dare say she is—and I don’t mind telling you, my dears, I’ve never laid eyes on the woman, it was Noël’s father as used to bring the children to visit with their old Aunt Betsy—he had a good heart, I’ll say that for him—as I say, she may be a fine lady, but from all I’ve heard, she won’t be satisfied with no tiny dower house and a retired life when he marries: ruling the roast is what that one’s been used to all her life!” She nodded terrifically.

“Perhaps she may go to live with one of the sisters, ma’am,” said Captain Lord Lucas soothingly. –No-one else was capable of speech at all, in fact Muzzie had her mouth wide agape.

Mrs Urqhart sniffed. “Perhaps is perhaps. Only if she was my little sister, me dear,” she said to Paul, “I’d think twice about giving her to Noël, so I would!”

The unfortunate Mr Ainsley went very red and murmured: “We all like Sir Noël very much, Mrs Urqhart, but I do not think that Gaetana affects him particularly. She had many admirers in London.”

“Aye, so I’ve heard, and I said to him: ‘Noël, you may take it from your old Aunt Betsy, from what you’ve said of the girl it sounds like she was only a-flirting with you, and I’m one as has done enough of that in me time to be able to tell!’“ She gave her rich chuckle.

“I wish I had known you when you were young, ma’am!” cried Hildy.

Mrs Urqhart smiled but said: “Ah, they would never have allowed you to speak to me.”—Muzzie at this point went very pink and slipped her hand into Uncky Cousin’s.—“For all he bought The Towers off that lord what gambled his inheritance away, my pa weren’t nothing but a tradesman, and could remember the days when his pa had nothing but a little shop in a back street! And indeed, though I seen her several times with her pretty friends, I never spoke a word to your mother in the whole time we lived at Lower Dittersford.”

“That’s terrible!” cried Hildy, very flushed.

“Nay, it’s naught but the way of the world, me dear,” said Mrs Urqhart, shaking her head. “And I dare say it would be hard to tell who was the happier, in the end, Miss Patty with her pretty friends and her pretty beaux, and her fine girls,”—she beamed at them—“or me and my Pumps, that was a weak little weed of a fellow like you never saw, when first I clapped eyes on him!”

“Mamma and Papa were very happy,” said Christabel, smiling at her, “though Papa died some twelve years ago.”

“Is that so, my dear? Well, I’m sorry to hear it. So your mamma is a widder lady, too? Well, don’t it seem strange?” she said with a sigh. “Pretty Miss Patty and me, both widders in our mid-years! –Be your Mamma grown stout, too, my dear?”

“Mamma has become rather stout, indeed,” said Christabel without a tremor. “I am sure she would be delighted to receive a call from you, Mrs Urqhart.”

Mrs Urqhart gave her a dry but kindly look. “It’s good manners in you to say so, Miss Maddern, but I’ve always been one as knows my place. I wouldn’t dream of calling at the Manor to put your mamma to the blush!”

“Nonsense, you would be most welcome, and you could be introduced to the peculiarities of our household, ma’am, and then you would see who is put to the blush!” said Paul with a kind laugh. “We have a parrot who speaks French and strongly supports Boney in that language, and a Spanish valet who will sing in his native tongue for you at the drop of a hat, and two horrible twins aged ten who will dissect a mole before your very eyes with the merest word of encouragement!”

“Yes: you have only to say ‘mole’, in fact!” said Hildy with a giggle. “And Bunch—that’s the girl—she’ll shoot a dove or two with a slingshot, should you say ‘dove’, into the bargain!”

Mrs Urqhart beamed at them. “Well, I own I have a fancy to see this parrot! Now, me and my Pumps had an Indian bird—you wouldn’t know them, me dears, we don’t have ’em in England, but he was called a miner, which I’ve always thought was a funny name for a bird, acos I never saw him dig for nothing in me life,”—here Mr Parkinson abruptly had to turn away and stare fixedly at the ruins—“and he could say ‘Where’s me dinner?’ like a Christian, and words in Hindoostanee, which is what the natives speak in India, which I won’t bore you with!” She beamed at them, panting a little. “But you can argify till it be ever so, and you won’t see me a-calling on your aunty!” She nodded the plumes at Paul. “But what I will say is, if you was to think it over and find you might like to call in at The Towers, complete with these twins and parrot,”—she twinkled at him—“then I wouldn’t say ‘No’!”

“Good! We shall all come!” cried Hildy eagerly.

Mrs Urqhart patted her arm. “You may come at any time, me dear, and we’ll chat about India as much you likes!”

“May I really? I shall drive over in the trap tomorrow!” gasped Hildy.

“Dearest, you cannot drive the trap such a way alone,” murmured Amabel.

“No, I do not think your driving is quite up to scratch,” agreed Paul.—Here a resigned expression appeared on Mrs Urqhart’s good-natured countenance, and Lucas Claveringham flushed a little.—“And besides, the trap is being repaired,” he added with a twinkle. “But there will be no need of traps at all, because we shall all ride over, it will be an opportunity for you girls to practise your riding!” he added with a laugh.

“Really? May we?” cried Hildy eagerly, quite as if he were her papa and not her cousin.

Paul looked at her a trifle wryly, feeling about seventy-five and hoary with it. “Yes, of course, Hildy. Blue Moon is eager for you to ride him, you know: that is what he expects of his new owner.”

Hildy went very red. “I am not really his owner,” she said in a tiny voice.

“¡Querida, of course you are! Did you not understand he was a gift?” cried Paul.

“No,” said Hildy huskily, tears starting to her eyes.

Christabel began in horror: “Cousin, you cannot mean—”

“Of course, of course! What is wrong with you all? Merde, I know, it is my inability to speak English correctly!” he cried.

Christabel glared at him, speechless.

“No,” he said with a smile: “of course Blue Moon is Hildy’s very own, and Dancer is your very own, dear Christa, and gentle little Dappled Dawn,”—he took Amabel’s hand gently with his free one and kissed it lightly, “is our dearest Amabel’s, and she is pining in the stables wondering why you do not ride her, Amabel!”

“Dappled Dawn!” breathed Muzzie. “What a lovely name!”

“I am so very unsure in the saddle, Cousin,” faltered Amabel. “And I did not like to— I did not understand that I might use her at any time, I mean, that she was for me to— And it is most generous of you, but really…” She looked helplessly at Christabel.

“We cannot accept,” said Christabel in a stifled voice. “We had no notion, Cousin, that you meant the horses to be gifts.”

“Besides, Mamma will never be able to afford to feed them,” said Hildy, almost in tears.

“Oh,” he said, disconcerted. “Well—well, if I pay for their feed and find you a groom—”

“No!” cried Christabel in anguish.

“Why not? If he can afford it, and I don’t suppose as he cain’t, the Ainsley Manor lands are the best in the county,” said Mrs Urqhart, who had been following the conversation with great interest and sympathy: “let him! It don’t never do to turn down a gentleman’s generous gifts, Miss Maddern,” she informed her kindly, “for it will only hurt his feelings in the end, and he won’t never understand such a thing as a lady’s scruples, you know, when all he’s wanting is for you to take the thing! Acos when all’s said and done they’re only men, ain’t they?”“

“That exactly what my mamma would say!” approved Gaetana, coming up to the old lady’s elbow. “And if you do not accept the horses instantly, Christa, I shall write her immediately and she will send you a good long scold! –How do you do, Mrs Urqhart?” she added. “I’m Gaetana Ainsley.”

“And I’m very pleased to meet you, Miss!” approved Mrs Urqhart, chuckling. “My, another one more like Sir Vyvyan than one of his own get!” she added.

“Yes, many of the cottagers say so,” agreed Gaetana serenely.

“Though you’ve got them Spaniard’s eyes, like your brother’s,” she noted keenly.

“Indeed, we have our mamma’s eyes.”

“I should like to meet her—in especial if she understands about gentlemen’s feelings and gifts!” she added with a laugh

“Indeed she does: she understands very much about gentlemen,” said Gaetana seriously. “—Christa, surely you do not truly intend to refuse your darling Dancer?”

“It is too much,” said Christabel, scarlet-faced.

“And now he is offering to get us a groom and pay for their feed, and with Marybelle’s and Floss’s horses that makes five, and it is far too much!” agreed Hildy, very teary.

Paul sighed. “Very well, shall we have a compromise? The horses are yours, but they may be stabled at the Manor when you are absent.”

“That sounds very fair!” said Lord Lucas with a smile.

“Indeed, ladies, you cannot jib at that!” agreed Sir Noël, his amber eyes twinkling.

“It is a reasonable compromise, indeed, Miss Maddern,” approved the Vicar.

“Yes, indeed,” said Susan. “It is precisely what my cousin does with the ponies he has bought for his best friend’s little girls.”

“I know!” cried Gaetana with a laugh. “They eat their heads off in his stables all—” Her voice faltered. “All year,” she said lamely. “Ned Adams mentioned it.”

“Yes,” said Susan simply, “though whenever he is at home Cousin Giles goes out into the home paddock himself and exercises them all on a lead rein. It is a very sweet sight: he on his big black, and the three fat ponies trotting along behind!”

Gaetana was very red. “I am sure,” she said in a stifled voice.

“Well, now, we’ve settled it!” declared Mrs Urqhart merrily.

“Indeed!” agreed Paul, smiling gaily but with an anxious look in his eyes. “Do you accept, Cousin Christabel?”

“What can I say? I accept very gratefully, Cousin,” replied Miss Maddern.

“Splendid!” cried Mrs Urqhart. “And you will ride them all over to see me, and we shall have a jolly time, I promise you! And if you should think it suitable for the young ladies, Miss Maddern,” she said on an anxious note, very evidently having seized who was in charge here, “I shall ask my woman to cook some of her special Indian sweetmeats for you all.”

“Agree, Miss Maddern!” urged Captain Lord Lucas with a laugh. “They are the most delicious things I have ever tasted!”

“We should be delighted to try them, Mrs Urqhart,” smiled Christabel.

“Tell her to make those round ones with rosewater, ma’am,” suggested Lord Lucas with a grin.

“No, no, old fellow, the yellow stuff she swears is carrots, with the nuts and silver cashoos on it!” cried his friend.

Mrs Urqhart chuckled complacently. “She shall make ’em all, bless you, aye, and some of them barfees, too—though they the ain’t the same without the buffalo milk. Was there ever such a pair of boys?” she added to the company with a proud smile, before anyone could get out so much as a gasp at the idea of buffalo milk.

“Indeed!” said Christabel, smiling very much.

“All boys like sweetmeats. I confess,” said Paul with a melting look, “that I am very partial to rosewater, myself!”

Mrs Urqhart shook all over. “You shall have ’em! Dozens of ’em!” she choked.

“I wish I might come,” said Muzzie wistfully.

The elderly lady gave her a sharp look. “Well, now, that wouldn’t do at all, would it, Missy? Your mamma would not approve, for well I knows as Lady Charleson is the strictest mamma in the district—aye, and quite right, too!” she said, nodding.

“I shall ask her,” said Muzzle, pouting.

“And so shall I!” declared Mr Charleson valiantly. “We should love to visit with you, ma’am. I say, you don’t still have this miner bird, do you?”

“No, alas. He died at a good old age—well, the fellow that sold him to us, he reckoned as he were sixty-eight then, only that was a bouncer, all these Indian fellows lie like nobody’s business. Only you gets used to it, it’s the way, out there. And nobody believes anybody else, so where’s the harm? No, but he were a good age, he went quite grey round the beak at the last, poor old Gentleman Jack! Don’t ask me why we called him that, young ladies and gentleman, it was my Pumps’s idea, and once he took a notion into his head no-one couldn’t never get it out! Gentleman Jack that bird were, to the day he died, bless him! And his last words were: ‘Where’s me dinner? Chai, chai; jooldee, jooldee!’ That means ‘Tea, tea, right quick!’” she said with a laugh and a sigh. “My word, old Gentleman Jack!”

“I have heard of a Gentleman Jim,” said Gaetana dubiously.

“Yes, but he’d be after Gentleman Jack’s time,” said Sir Noël with a twinkle.

“Indeed!” agreed Paul, laughing. “Well, may we escort you to view the best part of these ruins, Mrs Urqhart?”

“No, I thank you, Mr Ainsley, you may assist me to a seat, that’s what you may do! I said as I’d bring Lord Lucas, and so I have, but me and Noël has seen this old priory I dunnamany times!”

“Yes: when I was around sixteen or so—that was when Uncle and Aunt Urqhart returned from India,” explained Sir Noël, “I used to spend half of my school holidays at their house. The priory is quite an old haunt, indeed.”

Mrs Urqhart sat down on a large stone. “That it be! Him and my Timmy, they used to play at dacoits and I know not what in them bushes!”

Not asking what a dacoit was, though she meant to have it out of the old lady before long, Hildy sat down beside her and asked eagerly: “So you have children of your own, ma’am? Was your Timmy born in India?”

“Aye, that he was, bless him; and seven afore him that are all a-lying under the cruel grey dust out there as we speak,” she said with a sigh.

“Oh, I’m so sorry!” cried Hildy in distress.

Mrs Urqhart patted her hand and adjusted a slipping fur stole. “But I have three as lived, me deary, never you fret! And Tim’s a fine young man, now—and won’t let his old ma call him Timmy no more!” she added with a laugh.

“He runs the business, together with Uncle Urqhart’s former partner,” explained Sir Noël.

“Indeed he do! And my Bessy and Kitty, they’re both married and with families of their own! Though Kitty lives up north in a place called Yorkshire: I expect you’d have heard of that, Missy,” she said, “and it’s so far away, I don’t see her more than every second Christmas, maybe. She’s got a boy and two little girls, now. And Bessy would go back to India, though I warned her— Oh, well. She were born there and it’s more like home to her than England. And her little boy’s a fine, sturdy lad, so we must just pray as the climate don’t get him!” she said, nodding.

“Yes, indeed! And is her husband in the business, also?”

“No, Miss Hildy, he’s in the East India Company, has you heard of—?” Hildy was nodding eagerly. “Well, I never knew such a knowledgeable young lady!” she said pleasedly. “Yes, my Bessy’s man is a very fine fellow indeed, and slated to rise in the Company, you mark my words!”

“Good,” said Hildy simply. “And where do they live, Mrs Urqhart? Calcutta?”

She had pronounced it with the accent on the second syllable. Mrs Urqhart smiled. “Cal-cutta, that be, me dear, though I ain’t never heard an English person say it right. And it’s Bom-bay, not Bom-bay,” she added.

“Indeed? With the accent on the first syllable in both cases? That’s very interesting,” said Hildy thoughtfully.

“Aye, that it is, but I think we’re boring the company, me dear!” she said with a laugh, patting her knee. “My Bessy, she lives in a place called Cawnpore that I’m willing to bet me best necklace you ain’t never heard of, educated an’ all though you be! –Now, Noël, you may take Lord Lucas and show him the best nooks and crannies, only do not be too long about it, I declare I am fair sharp-set and have been thinking of me luncheon this past hour!”

Sir Noël bowed and led Gaetana and Lord Lucas away, Miss Maddern electing to accompany them. Paul, though he would have liked to stay and talk with the fascinating Mrs Urqhart, went too, holding Christabel’s arm possessively. Muzzie, who was visibly impressed with the two gentlemen, also went along, as Lord Lucas bowed and offered her his arm. She flushed up and squeaked: “Oh! I have never held a gentleman’s arm affore, only a brother’s or an uncky’s! Oh, thank you, Lord Lucas!” As they went she could be heard assuring Christabel that the name “Dancer” was a ’licious name for a horse, and perhaps they could ride out together, and either she would ride darlingest Daffa-Down-Dilly her very self, or if Uncky Cousin asserlutely insisted to have him, then—

Hildy sighed.

“Aye, well, most of ’em are brainless at that age,” said Mrs Urqhart drily.

“Yes!” she gasped.

“Now, you tell me about yourself, me dear,” said the old lady, patting her knee, as Susan and Dorothea went to gather up their sketching things and Mr Parkinson, Amabel and Mr O’Flynn lent their aid. “Which of these young gentlemen do you favour, mm?”

Hildy went very red. “Not any of them, really. Well, Mr Parkinson is… But he is a prude!” she burst out.

“Hm. Prettiest fellow I ever clapped eyes on, and I’ve seen a few in me time. Only it’s what’s inside that counts, not a pretty face,” said Betsy Urqhart on a grim note.

“Yes. What is inside,” said Hildy with a sigh, “is extremely proper and conventional, though thoroughly admirable.”

“Sounds a dead bore,” said Mrs Urqhart, feeling in her reticule. “Have a nut, me dear.”

Surprized but not unwilling, Hildy took a nut. “Thank you. Well, he is an extremely well-read and intelligent man... But he’s a parson,” she added glumly.

“I wouldn’t have him, then. Seen too many parsons’ wives. Put ’em last after God and their parishioners, if they’re good parsons, that is, and the end of it is, the woman wears herself out for nothing at all, because what thanks do you get from a man as thinks it’s your bounden duty to be his doormat, me dear? None at all!”

Hildy gulped. “No. Well, I wouldn’t say that he would go that far, but... I don’t think I could do it. One would have to be good all the time, and—and subordinate one’s will to his.”

Mrs Urqhart chewed her nut thoughtfully. “Aye. Or to his idea of what his Maker’s will is, eh?”

“Yes! Oh, how very percipient of you, Mrs Urqhart!” she cried.

“Well, I’ve lived a longish time, me dear, and seen a fair bit, and thank God I’ve still got the brains as I were born with. Pa always did say I’d a better head on me than any man in his office!” she said with a laugh.

“I’m sure!” agreed Hildy eagerly.

“Aye, well, it would be strange if I had not managed to learn a little from life, would it not? And you mustn’t mind my outspokenness,” she said with an anxious look, “for I’m a plain-speaking, plain woman.”

“No, I like it: it’s such a relief,” said Hildy with a deep sigh.

Mrs Urqhart patted her knee again. “Aye. Mealy-mouthed, is he?”

“Yes, very; and I do not understand,” cried Hildy, tears starting to her eyes: “how a person of his intelligence can be so! I know he sees the hypocrisy of mere social forms, for he once admitted as much to me! But why must he act all the time as if such things matter, and as if I should think such things matter?”

“Well, I dunno, me dear: that’s a bit deep for me, acos I never had no book-learning. But I’d say as he can’t help it: it do sound as if it be ingrained in him, like.”

“Yes,” she said glumly.

“Don’t have him,” she said, patting her knee hard. “Oops, here he comes! Well, what I say is,” she added loudly. “there ain’t nothing like a nut, me dear, to satisfy the stomach when it be sharp-set, even though my Pumps would maintain there weren’t nothing to choose between me and Gentleman Jack, when it came to the nuts!”

At this Hildy gave a loud giggle, and Mrs Urqhart beamed upon her.

“Well!” said Christabel at the end of the day, sinking onto a chair in the sitting-room.

Paul had followed her, having removed his hat and gloves. He said with a twinkle: “Do you not wish to accompany the other young ladies upstairs to change, my dear?”

“I do not have the mental energy. What an extraordinary woman Mrs Urqhart is!”

“Is she not?” he said, pulling up a chair beside hers.

“Hildy was so taken with her: I suppose it will be another Old Tom affair: Mamma will disapprove deeply and it will be I who will have to enforce—” Christabel put her hand over her mouth.

“Dearest Christa,” said Paul in a very low voice: “you may say anything to me; I will never repeat a word you say to a living soul, and I will never criticize a word of yours by so much as a look. You must know you have all my—” his voice trembled; “all my respect.”

“Thank you,” she said faintly.

There was a short silence.

“But I do think,” said Christabel, rallying, “that never being criticized by so much as a look would be shockingly bad for my character!”

Paul smiled a little. “Nothing could be,” he murmured.

Christabel blushed and was silent.

“Shall you come tomorrow?” he said.

“I should like to, very much. She may be very vulgar—well, let us admit it, she is; but she is not without considerable intelligence, as well as native shrewdness; and, I would say, entirely good-hearted.”

“Indeed.”

“Though perhaps it is merely greed talking,” said Christabel with a twinkle.

“Sugar, butter, milk and rosewater? Never!” he protested.

“You forget the nuts and—what was the other thing that was in them? Carrots?” She laughed, but then said cautiously: “Paul, did you—did you notice anything about Hildy and Mr Parkinson?”

Paul looked dry. “Yes: I would not say he appeared encouraged, today. Well, you have had my opinion of him,” he added wryly.

Christabel chewed her lip.

“Well?” he said, his dark eyes sparkling.

“You are right,” she admitted: “of course he is a prude. I have heard Hildy herself say so, you are not alone in that opinion. But—but he is such an admirable person, Paul!”

“Sí, sí,” he said, leaning forward and clasping both her hands in his: “An admirable person, who would make Hildy very unhappy by desiring of her entirely the wrong things; and whom she would make very unhappy, too, for even if she attempted to be as he wished, I do not think she could. Well, we have seen how she tends to—to burst out, in his presence, have we not?”

“Yes. What did Floss actually say to you?” she asked on a sharper note.

“It was a confidence,” he said, kissing the tips of her fingers and slowly releasing them.

“Oh,” said Miss Maddern, very pink.

“But I can say that only a prude and a gudgeon could possibly have buh-been shuh-shocked!” gasped Paul, collapsing in a gale of laughter.

Christabel watched him uncertainly,

“O, là, là, I have been holding that in all day!” he gasped.

“Yes. Paul, is that a—a Spanish expression?”

“What?” he said blankly.

“That ‘Oh law, law’—I cannot say it, you seem to produce the sound right at the back of your throat.”

“No! Petite imbécile! It is French! And usually said by somewhat low persons, of whom that back A is most typical,” he said with a twinkle.

“Surely it is an O?”

“No, but the more it sounds like an O, the more vulgar it is!” he choked.

“I see.”

Paul twinkled merrily at her. After a moment Christabel flushed up and looked away.

“I shall speak to Tia Patty about Mrs Urqhart,” he said. “I think, with so few neighbours in the Dittersford area, I shall represent to her the propriety of encouraging one of the few we do have.”

“Ye-es... Well, there is Lady Charleson,” she said dubiously.

Paul shuddered.

“And presumably Mrs Purdue: she has left cards.”

“I have it on excellent authority that Mr Purdue is a man who transports poachers: we do not wish to know a person of that ilk.”

“No-o... Do you not object to poaching, then?”

“Darling Christa, I would rather see every animal and bird on my lands taken, than send a single soul to Botany Bay on one of those vessels,” he said with a shudder.

“Oh. Are the transport ships so very dreadful?”

“Yes. Pa and I once— Well, never mind, the captain in question did not understand that what he was saying horrified us both to the core, and had he realized it, I dare say he would have put us down as a pair of very odd Dagoes,” he said with a sigh. “But that aside, Mrs Purdue appears to be a bosom bow of Lady Charleson, and even little Muzzie admits her to be ‘a very strict lady’. I doubt if she and your mamma will have much in common.”

“No,” she murmured, frowning thoughtfully.

“What is it?”

“Nothing. Well, usually gentlemen speak so casually of—of having poachers transported, or of hanging or—or of punishing the lower classes in general.”

Paul looked at her dubiously.

“I remember once walking in the woods with Papa and Hal—it was not very long before Papa died, because we did not go very far and he was muffled up in fur rugs—and we heard a shot and Hal cried that it was Old Tom poaching on our land, and Papa said: ‘Good luck to him. That reminds me, Christabel, pray remind me when we reach home to ask for a package of provisions for the old fellow: the poor people are finding it a hard winter,’ or words to that effect, you know; and Hal cried: ‘Feed a dirty old poacher? I would string him up!’ And Papa said: “Harold, never let me hear a son of mine speak words like that again, have I not told you we share a common humanity?’ And Hal went very sulky, he was ever prone to do so if reproved, and said: ‘But he is a thief, Papa,’ and Papa said that so would Hal be, if he had been born in Old Tom’s circumstances, and never to forget how fortunate he was. And that there was a letter in his desk—” Christabel broke off, swallowing hard.

“My dearest, do not distress yourself,” said Paul softly. “I should like above all things to have known your papa. The more I hear of him the more I am convinced how truly admirable he was.”

Christabel blew her nose. “Mamma once said to me he was soft, and then she cried and said she would rather have had him soft than have had any other man at all,” she recalled.

He smiled a little ruefully. “Mm.”

“Oh, dear, I must go up, I suppose I look a fright.”

Paul rose and held out his hand. “No, you do not look a fright. So you would wish me to be lenient towards the miscreants who steal my rabbits and birds, then, dear one?”

“Yes,” said Miss Maddern, flushing. “I would. If my wishes enter into it!” she added with a mad little laugh.

Paul kissed her hand formally, and bowed. “They are everything.”

“Heavens!” said Miss Maddern faintly.

“Believe me.”

“I— You are being absurd! I must go, it must be near upon dinnertime and Mamma will wish to see me.”

Paul smiled a little and went over to the door, opening it and bowing to her as she passed.

“Thank you,” she said, not meeting his eyes.

He closed the door after her, smiling, went over to a sofa and threw himself on it with a laugh, linking his hands behind his head. “Was he soft?” he said to the ceiling. “Well, mayhap a partiality for soft men is in her blood, then!”

“Very well, dear Paul, if you wish it,” said Mrs Maddern next morning, straightening her lace cap and silently thanking the Lord—not to say Mason—that she was wearing it and not that very ugly old nightcap that was so comfortable.

Paul was sitting unaffectedly on the edge of her bed. He had apparently never thought to question whether this was possibly not the done thing in English circles: Mrs Maddern could not quite work out if he had got it from his papa, who might have absorbed it at his mamma’s knee, not to say his grandmamma’s, for in Grandmamma Ainsley’s day it had been the thing for gentlemen to visit grand ladies in their private apartments after their hair was powdered and to advise on the placing of patches and such, or if it was merely a foreign habit that Paul had picked up from his mamma. In the latter case she would not like to hurt his feelings by criticizing it, so she never had. Besides, it was rather a nice feeling to have him there. Only she was very glad she had her pretty cap on this morning.

“I think it would make a rather lonely elderly lady very happy, Tia Patty,” he said, smiling at her. “She has explained that her one surviving son lives in London, and one of her daughters is in India and the other in Yorkshire. And I gathered that Sir Noël Amory’s mamma does not encourage her family to visit the poor soul. Though he himself certainly appears very fond of her.”

“Good gracious, then she is all alone in that big old house?”

“Yes. Well, she has her faithful servants, including an Indian woman who makes native sweetmeats, but—yes. It must be a lonely existence: it is very clear the grand ladies of Dittersford will not demean themselves to notice the poor old dear.”

There was a short silence.

“What grand ladies, pray?” enquired Patty Ainsley Maddern grimly.

“Oh, Lady Charleson, of course—I suppose she is more or less the squire’s lady hereabouts,” he added carelessly—Mrs Maddern’s bosom swelled alarmingly—“and a Mrs Purdue, who from little Muzzie Charleson’s account is terrifyingly high in the instep and has Lady Charleson quite under her thumb.”

Mrs Maddern took a deep breath. “Purdue?”

“Sí.”

There was a short silence.

“The name was not known in either Dittersford or Daynesford in my day,” said Patty Ainsley Maddern grimly.

“Oh, so she is quite a newcomer? I think Eric Charleson did mention,” he said, wrinkling his high olive brow, “that Mr Purdue built his house quite recently—”

Mrs Maddern gave a terrific snort.

“Somewhere near Lower Dittersford, I think,” said Paul calmly.

“Then it is in a swamp!” she said awfully.

“I believe it is very damp, thereabouts.”

“Damp! My dear boy, the cottages are under water in winter, and your grandpapa took one look at the people in the tied cottages in those parts and got upon his horse immediate and rode to see Mr Shillabeer himself, and told him to his face it would not do! And I will say this for the man, he rode out with your grandpapa to see for himself and had the families out that very day!”

“Good. –Mr Shillabeer?” he said weakly.

“Her father, of course! The man who bought The Towers!”

“Oh, I see. It is not a very—very elegant name,” he said, swallowing.

“Smacks of the shop,” said Mrs Maddern with a sniff.

“Sí,” he agreed unhappily.

“Never mind that!” she said with great determination. “The woman cannot help who her father was, and at all events I never heard any ill of him! But if this Purdue has built down there, you may wager your life there is damp in the linen cupboard before November is out!”

“Very like,” said Paul, a trifle weakly.

“Urqhart...” said Mrs Maddern thoughtfully.

“Yes. She mentioned at one point,” said Paul, refraining from smiling, “that the spelling is unusual, lacking an U. The Amorys are cousins, of course.”

“Ssh!” Mrs Maddern held up a commanding hand. “How old is she?” she said at last.

“Why—er—rather older than you, I think, Tia Patty,” he stumbled. “Though she appears very much older: the rigours of India upon the complexion, you know.”—Mrs Maddern smiled little, fluffed up her wrap, and nodded.—“Er, she remembers you the year of your come-out, when she was but a young woman herself.”

“Mm. So this Urqhart... Eastern imports, did you say, my dear?”

“Oh—yes, but that was the uncle’s business, Tia Patty: I am afraid I am not sure whether the uncle was a Shillabeer or not. But Mr Urqhart was originally in the Army.”

“Not little Timmy Urqhart!” she gasped.

“Er—well, her son is certainly called Timmy, so possibly—”

“It must be! Little Timmy Urqhart! My dear, his sister was a great friend of our Cousin Sophia’s, though she lives much retired, now, Kensington or some such... I believe he was a connection of the Amorys, yes... So little Timmy became a nabob? My dear, it is almost inconceivable!”

“Mrs Urqhart tells us he had a great head for business, Tia Patty.”

“Well, he certainly did not have a great head for wine!” she said with a laugh. “And caterwaul! You never heard anything like it, my love! He was used to strum on—now, it was not a guitar: your guitar is so pretty... No, I have it: a mandolin: he was used to strum on it, and caterwaul his heart out! Little Timmy Urqhart! He was an ensign, my dear, the most unfledged thing you ever saw! And then I believe he did go out to India… Yes, it must be he! How extraordinary! Ring the bell for Mason, dearest boy, I shall get up and write a line to Sophia directly! How she will laugh! Little Timmy a nabob! And you say he became immensely portly in later life, my dear?”

“Well, Mrs Urqhart said he was the size of a balloon,” he said in an apologetic tone.

Mrs Maddern laughed heartily. “He had the poorest little spindle-shanks you ever set eyes on, my dear! In those days it was all knee-breeches, not the pretty pantaloons like the young men wear nowadays,” she said, eyeing his legs complacently—Paul went rather red and repressed an urge to re-cross them—“but nevertheless, if you think pantaloons may show up a poor leg, you would have stared to see poor little Ensign Urqhart in his stockings! Put ’em together and there still would not have been one decent calf!” She laughed heartily once more, and then blew her nose as heartily.

“So you will permit us to visit?” ventured Paul, still not absolutely sure what she had decided.

“My dearest boy! Certainly you must visit the poor creature! And I shall call myself on Monday, as ever was! And you may tell her from me,” said Mrs Maddern in a grim voice, “that in my dear aunt’s day a Purdue would not have set foot in this house, and I see no reason to change that state of affairs!” She nodded terrifically.

Rather stunned, Paul said meekly: “Sí, Tia Patty. I think Mrs Urqhart will be very thrilled to receive a call from you. It sounded as if she had always admired you from afar: she spoke of your beauty, you know.”—Mrs Maddern bridled a little and patted the lacy cap.—“But you must not get the impression that she is anything but vulgar, you know,” he said anxiously.

She smiled at him. “No, my love, you have made that quite plain, but never fear me, I shall be kind to the creature. –Lord, and I wager she managed the poor little fellow till he didn’t know if he was on his head or his heels! Little Timmy Urqhart!”

Paul went downstairs, smiling. Gaetana and Hildy were in the morning room, waiting to hear their fate. They laughed and clapped their hands at the glad tidings. Though Hildy did then note with awful irony: “I suppose next you will inform us that she is about to persuade Lady Charleson to let ickle Muzzie accompany us!”

“Well, possibly not this visit. But I would not take any wagers about the next,” he said smoothly.

“Paul!” screamed Gaetana. “You couldn’t! Not even you!”

Hildy’s eyes narrowed. “If you do it…” she said slowly. “Yes: I will guarantee to steal you one of Mr Stalling’s apricots off those espaliered trees in the vicarage garden that loomed so large in the silly man’s last sermon!”

“Hildy!” gasped Gaetana, half laughing, half horrified.

“Done!” choked Paul ecstatically.

Hildy winked at them, and went out.

“Paul, you would not let her!”

“Pooh, of course I would. Mrs Stalling believes her to be a young lady, you know: it will be easy, Hildy will go to call at the vicarage on some charitable excuse, and she will go out into the garden carrying her reticule, chatting airily—”

Gaetana grabbed up a cushion and beat him unmercifully.

“I give in!” he gasped at last. “I tell you what,” he said in her ear: “I only hope Holy Hilary is still here when she does it: I should like to see his face!”

“I thought you liked him?”

“Sí, sí, little kitten, I like and admire him for all his excellent qualities! But I am very sure those excellent qualities would make our little Hildy very miserable!”

“Yes,” said Gaetana glumly, “I agree. It’s all very difficult... I know she thinks poor Sir Julian is rather stupid, and I’m afraid he is.”

“Yes, though he is a very good fellow, with no pretensions about him.”

“Sí. But is that enough?”

“I don’t know, little kitten,” he said, kissing her forehead gently. “I only know that Holy Hilary is too much!”

About ten minutes later, Hildy verified this for herself. “Of course I shall go!” she shouted furiously in the Manor’s apology for a shrubbery.

“But Miss Hildegarde, I can understand your wish to gratify an elderly lady’s whim, and I am sure, as you say, there is no harm in her, but— Well, a person of her vulgarity? What will the neighbours think?” said Mr Parkinson, swallowing.

“What will the NEIGHBOURS think?” shouted Hildy furiously. “If you were thinking of the Marquis of Crabapple or the murderous Mr Purdue, sir, you may think again! And you are the man who approved of my visiting Old Tom! I never heard such a piece of sophistry in all my life!”

The Vicar had, in the light of Miss Hildegarde’s subsequent conduct, been mulling over that episode and he did not feel that his opinions had been stated with the crystal clarity they might have been. Indeed, he feared he had given the wrong impression entirely. Or so he now believed. What he did not understand was that his terror at Hildy’s more recent unconventional behaviour was now leading him to deny his former admiration for her actions and that in the present, very trivial case, he was testing both her respect for his ideas and her feelings towards him as a man. He did not understand, either, that these last two were not necessarily harnessed in parallel in Hildegarde Maddern.

“I did not approve of your visiting him as such, Miss Hildegarde,” he said very stiffly: “I approved of an act of Christian charity. It is not at all the same case.”

“You hypocrite!” shouted Hildy.

“Miss Hildegarde, you did not ask me at the time whether it was a suitable thing for a young lady to do, as I recall.”

“I do not wish to hear what you recall! You recall things as it seems to suit you, sir!” she cried.

“I shall always admire you for having done it,” he said.

“What are you TALKING about?” she cried.

“It was an admirable thing to have done. That does not mean it was at all a suitable thing for one of your age or station. Can you not see the two things are not at all the same?” he said miserably.

“NO!” shouted Hildy.

The Vicar took a deep breath. “Miss Hildegarde, in this particular instance, at all events, there is no poverty or want in the case, and Mrs Urqhart seems to be happy in her own circle of acquaintance. Could you not for once consider appearances? At least set an example to your little sisters and to young Miss Charleson?”

“WHAT?” screamed Hildy. “Muzzie Charleson is so muzzy in the head she would not recognize an example if it stood up before her and danced a galop!”

“Miss Hildegarde, it does not become you—”

“No, and it does not become you to talk to me like a grandfather: you are making yourself ridiculous, sir,” said Hildegarde, suddenly very cold. “My mamma has approved the expedition—and even if she had not,” she added evilly, “I would go, because I like Mrs Urqhart very much, she is by far the most interesting person I have met THIS TWELVEMONTH!”—suddenly very loud indeed.

“I shall leave you, there is no talking with you when you are this mood,” he said, very white around the lips.

“Pooh! You have no fighting spirit!” she sneered.

“That is very true, Miss Hildegarde: I do not approve of fisticuffs,” he said tightly, turning on his heel.

“PIKER!” shouted Hildy at the top of her lungs.

... “Cor,” concluded Bungo thoughtfully under his bush when the sound of their footsteps had died away.

“Sí,” agreed Bunch.

The twins were not there in order to spy on their elders: they had very little interest in the goings-on of their elders. They were there to discover whether what Harry Higgs claimed was a rat-run really was, or if it was the walkway of something more mundane, such as a hedgehog—though they would not have been averse to seeing one of those, either. The notion that it was merely a coincidental narrow, meandering gap in the grasses and that the head gardener had been pulling their legs had not crossed their minds.

“Why did he let her bawl him out like that? I thought he had more spirit!” Bungo said disgustedly.

“Aucune idée.” Bunch produced something from a pocket in her petticoat. “Want one?”

“Gracias.”

The twins chewed olives reflectively.

“I thought,” said Bunch, spitting her pit out, “that she might marry him.”

“Ugh,” said Bungo automatically.

“No, it’d be good: he’d let us ride Lightning and drive his trap.”

“Ye-es... I expect you have to pray a lot in his house, though.”

Bunch thought it over. “Yes. I like the Manor better, really.”

“Me, too. –Want half?” Bungo produced a battered, half-ripe plum from his breeches pocket.

“Gracias.”

The twins ate plum reflectively.

“I wish that old lady still had the miner bird,” said Bunch glumly.

“Me too. –Floss says Pierrot said it the other day. Only I think it was all in her mind,” said Bungo glumly.

“Sí, she isn’t never going to get to drive the Marquis of Crabapple’s team, and you’re going to be in debt to Deering if you live to be a hundred, Bungo!”

“Sí. Well, he’ll be dead afore then. Only I know what you mean,” he said dully.

They waited, but no rats came.

“At least it’ll be a decent ride,” said Bunch.

“What? Oh, over to Lower Dittersford: sí. Did you believe what Paul said about the sweetmeats?” he asked optimistically.

“No! Imbecile! It was one of his jokes!” she cried.

“Sí, sí,” he allowed glumly.

“¡Madre de Dios!” he cried.

Bunch just goggled.

“Oh, Mrs Urqhart, what a magnificent display!” said Christabel with a little laugh, looking at the gleaming brass trays spread with sweetmeats in palest green and pink, bright saffron, soft cream, and shining toffee-brown. Added to which, the trays were wreathed with flowers, the whole effect being very beautiful.

“Now, maybe I shouldn’t explain what they be, until you’ve tasted ’em, my loves!” said Mrs Urqhart, beaming all over her round, painted face.

Bunch said excitedly in Spanish: “Look, Bungo, these are the squiggly things Francisco made once for a big holy day! Remember?”

“¡Sí! All in syrup!” he gasped.

“What are they saying?” asked Mrs Urqhart with interest. “Don’t it sound different from Hindoostanee?” she added to her beaming servant.

The woman giggled, pulling her saree a little further over her face. “Feringhee talk, Urqhart Begum!”

“Aye, and don’t you call me that, you heathen, it makes me feel an hundred! And run and get the tea-tray—chai, chai, jooldee! Acos we don’t want the water all cold when it gets here, we ain’t at home now, you know! –Well,” she said to the company, “I say we ain’t at home to the poor creature, but Lord knows me and poor old Ayah have been back here now nigh a many years as I were out in India.”

“Is that her name?” asked Hildy with interest. “Ayah?”

“Lord, no, deary, that’s what she is! She was my Timmy’s ayah, and all his brothers and sisters, too!”

“Like Berthe!” cried Maria.

“Is that your nursey, pretty one?”—Maria nodded hard.—“Aye, that’s right, my dear, that’s Ayah,” agreed the old lady, twinkling at her. “But her own name’s Bapsee, ain’t that a heathen name you?”

“I think it’s pretty,” said Maria shyly. “Bungo and Bunch were saying this sweetmeat is very like a Spanish one that our servant made us once,” she explained.

“What, these jullerbees? Land’s sake, is that so? You gets these all over the East, dear, though I wouldn’t recommend them as you sees in the dirty bazaars!”

“It’s a very sweet syrup, no?” said Paul. Mrs Urqhart nodded and he said: “Yes, I think it is the same. How fascinating, it must be the Moorish influence.”

“Well, you’ve lost me there!” she said with her frank laugh.

“They were Arabs, though,” said Hildy, frowning.

“Arabic speakers, mm. But possibly it is a Persian sweetmeat, let us not forget the Persians conquered India—that was the great Moghul Empire, you know.”

“Of course!” said Hildy, staring at the yellow-brown spirals in their dish of syrup. “Ooh, it makes you feel all shivery!”

“Well, it ain’t too warm, not to one of my thin blood; I dare say we could build up the fire,” said the old lady, hugging her magnificent Cashmere shawl to her and looking anxiously at Hildy.

“No, no, I am very warm, thank you, Mrs Urqhart!” she said with a laugh. “It is just the thought that here we are, about to eat a sweetmeat that is possibly a thousand years old and from thousands of miles away!”

“Well, nothing in my kitchen ain’t a thousand years old!” she said with a twinkle in her eye. Hildy gave a giggle. “Aye, but I takes your point, me deary. Now, them Moghuls, that’d be this Shah Jehan and his lot, wouldn’t it?”—The company stared blankly at her.—“The one as built the Taj Mahal? Me and Pumps, we rode on an elephant from Delhi to Agra to see it, and it’s certainly a beautiful sight, but them natives—” She sighed, shaking her head. “Two pools, it’s meant to have outside it, great long ones all filled with water, like so as the building would reflect in them, and they were both as dry as dust and dirty like you wouldn’t believe! Run down, that’s what that country is,” she said, shaking her head again. “No go in ’em. Fatalism, that’s what Pumps said it were. Fatalism.”

“‘Let it be as Allah wills,’” said Paul thoughtfully.

“Yes, and the idea of reincarnation—” began Hildy.

“Tell us about the elephant!” cried the twins.

“Well,” said Mrs Urqhart with a twinkle, “here is Ayah with the chai, so if no-one minds, we shall eat first and then I’ll tell you all about the elephant, and about Shah Jehan, too—you ain’t never heard of him, has you, Miss Hildy, for all your book-learning?”—Hildy shook her head mutely.—“It’s one of the great love stories of India, even if he were a heathen,” she said complacently. “Well, I’ll tell you all about him, too!”

Which she did, and much more; and the Madderns and Ainsleys came away from the dark old house that was The Towers with their heads spinning with tales of fabled princesses and paan, of thieving baboos and cunning dhobee-wallahs, of wise saddhoos clad in rags—or nothing at all, of cloistered ladies in heavily veiled palanquins, some on their painted elephants and some carried by sweating bearers, of tigers, leopards and monkeys, of strange fruits, nimboo panee and rusgoollahs, of jewelled nights—not to say real jewels, Mrs Urqhart, herself gaily bedecked, had opened up her jewel cases for the young ladies’ amazed eyes—of gallant officers and gauzy nautch dancers, of snake charmers and— All the mysteries and marvels that were India, indeed.

“I’m definitely going to join the Company,” said Bungo sturdily as they rode slowly home.

“Pooh: you only want to stuff yourself on sweetmeats for the rest of your life!” said his twin crossly.

“I do not! I shall be an administrator and hunt tigers and—and show the people the law!” he cried.

“You’ll have to learn how to spell first,” noted Paul detachedly.

“That is most unworthy of you, Cousin Paul. I think Bungo would make a splendid administrator, and to join the East India Company is a most worthy ambition,” said Christabel firmly.

“Yes,” agreed Bungo. “Also I would have three bearers in white uniforms and—and things on their heads like Mrs Urqhart’s butler, and a private elephant!”

“Private elephants do not come cheap,” said Gaetana with a twinkle in her eye. “Let us not forget that Mrs Urqhart’s husband and uncle were after all not servants of the East India Company, but wealthy merchants.”

“Yes; I should like to see those Calcutta warehouses,” said Hildy wistfully.

“And I. But India sounds terribly hot,” said Amabel.

“Ye-es... Though she said it was cooler in the hills,” replied Hildy.

“True,” agreed Christabel briskly. “But did you not remark how terribly overheated her sitting-room was, and how she said she could never get the house warm in winter? I think she must be used to a climate much hotter than any of us can imagine.”

“Sí. Can you remember summer in Spain, Paul?” asked Bunch.

“No,” he said, shaking his head. “I was only tiny when we left. But Marinela assures me I used to play in the courtyards in the sun in a state of complete undress!”

Christabel glanced at the handsome young man sitting easily on his horse and her mind suddenly filled with a sharp vision of a plump little olive-skinned boy child, running naked in the sun. She swallowed convulsively, tears starting to her eyes.

The others were agreeing that India must be even hotter than Spain and that though aspects of it sounded wonderfully Romantick, it was no place for English people, and it was scarcely to be wondered at that poor Mrs Urqhart had buried seven children there—but Christabel did not hear them.

“Good gracious me!” gasped Mrs Maddern when they returned and poured forth their bounty. Both verbal and physical.

“Tia Patty, she’s been on an elephant!” shouted Bungo.

“And on a camel!” shouted Bunch.

“Her husband shot a tiger!” cried Bungo.

“And she has the skin, we sat on it, Tia Patty: it’s true!” cried Bunch.

“Hush, children, hush!” she begged, laughing and clapping her hands over her ears.

“My dear Amabel, what is it?” gasped Mrs Parkinson, unrolling the exquisite thing that Amabel, looking sheepish, had laid before the two ladies.

“It is called a saree, Mrs Parkinson: the Indian ladies drape it round them in the most curious fashion: they have no notion of cutting cloth as we do.”

Mrs Parkinson lifted the shimmering primrose silk in awe.

“Dearest, you should not have accepted it!” gasped Mrs Maddern. “It must be worth a fortune! I have never seen silk of this quality!”

“Look at the trim!” gasped Mrs Parkinson.

“Gold thread,” said Amabel. “Um, she would not take a ‘no’, Mamma. I did try to insist.”

Mrs Parkinson draped it against Amabel’s shoulder. The palest primrose silk was embroidered with tiny medallions of the gold thread to match the heavy edging and the—

“Look at this end!” gasped Mrs Parkinson. “Why, feel the weight of it!”

“The servant showed us how they wear it, with the embroidered end falling over the shoulder,” said Christabel on a regretful note. “It would not do, I suppose.”

“Look what she gave me!” shouted Bunch.

Mrs Maddern blenched at the sight of an elaborately carved ivory dagger.

“It is but a toy,” lied Paul smoothly.

“Mine’s better!” boasted Bungo, whipping out a silver pistol.

Mrs Maddern shrieked, and fell back against her sofa pillows.

“It has been stoppered, do not worry, Tia Patty, he could not harm so much as a fly with it. Mrs Urqhart’s husband was given it by an Indian prince, for whom it was made: see the elaborate chasing of the handpiece?”—Mrs Maddern nodded feebly.—“But I doubt if it could ever have fired straight,” finished Paul with a twinkle.

“Pooh, it did, too: she said the prince shot a faithless servant with it!” shouted Bungo angrily.

“Ugh!” gasped Mrs Parkinson, what time Mrs Maddern looked at Paul in dismay.

“Well, it is a very old land and I dare say there are few objects in it that are not steeped in blood, one way or another,” he said calmly.

“It—it was very kind of her,” faltered Mrs Maddern.

“Tia Patty, imagine riding on an elephant!” said Bungo eagerly. “One is very high up, and it sways, you know!”

Mrs Maddern shuddered and closed her eyes.

“And a camel sways, too: Mrs Urqhart says it is the most sickening motion imaginable: lurch—forward; lurch—forward,” said Bunch, lurching round Mrs Maddern’s boudoir, where the two ladies had been resting in the absence of the younger members of the house party.

“Stop!” gasped Mrs Parkinson, gulping and sitting down suddenly, abandoning Amabel’s silk.

Dorothea, who had remained behind, feeling rather tired after yesterday’s outing, said faintly: “Yes, indeed, Bunch. Although I had the most comfortable circumstances across the Channel that could be hoped for, really that sort of motion…” She closed her eyes. Miss Dewesbury, who had also stayed behind, partly to keep her company, partly because she felt that her mamma would not care for her to visit, put a comforting hand on hers.

“Now see what you have done!” said Maria crossly to her crestfallen little sister.

“I only—”

“Hush, hush, my dears! Come and sit by me, twins—yes, one on each side,” said Mrs Maddern, putting a plump arm round each of them, “and tell me one at a time what you had to eat, and—and about the elephants and camels. But no more lurching, please, Elinor, dearest. And you may start because you are a girl, even if you are not the very youngest!” she added with a smile.

Bunch took a huge breath and plunged into narrative.

... “Dearest, you should not really have let her!” said Mrs Maddern with a faint laugh after the room had cleared at last and she was alone with her two elder daughters, Dorothea, and Mrs Parkinson.

“Mamma, I could not prevent her, she is like—like the car of Juggernaut!” said Christabel with awe in her voice.

“Dearest, I have no notion what you mean!”

“She—she rolls over every objection laid in her path, Mamma, like a—a tremendous force! It was like trying to hold back the ocean!”

“Yes, Mamma: we really did try to say it was far too generous of her. Is not this silk gauze exquisite?” said Amabel, holding up another length.

“Yes, but my dears, even in the finest silk warehouses in London— Oh, dear!” she said, half laughing, half vexed.

“Christa must have it, with these pink flowers on it none of us could wear it, and the blue will not do for us, either,” Amabel decided.

Christabel, blushing, murmured: “They are not all flowers, Amabel, look again.”

Amabel looked again. “Butterflies!” she gasped. “Oh, look, Mamma, they are exquisite!”

Mrs Maddern fingered the stuff cautiously. “Is the design painted on?”

“I do not know,” admitted Christabel. “It—it is very pretty, but could one wear a gown of pink and turquoise flowers and butterflies on blue?”

“This is gold,” said Mrs Maddern, touching the gilt edges to the butterflies.

“Mm.”

“Christa, you must wear it, it is exquisite!”

“For a ball dress!” urged Amabel. “With your sapphire earrings, dearest!”

Christabel swallowed.

“It would not be too much, you have the height for it, dearest Christa!” urged Dorothea.

“We shall have it made up in London,” said Mrs Maddern very firmly, folding it carefully. “And what did she wear herself, my dears?”

“She feels the cold,” murmured Amabel faintly, not looking at her sister.

“It is quite a mild day!” she cried in astonishment. “Harry Higgs was telling me but yesterday that this is one of the coolest summers for many a long year, and we cannot expect a great crop from the orchard, but we had the casement flung wide in here for I dare say half an hour!”

“To a person who has lived in tropic climes, it cannot have been a mild day, Mamma,” said Christabel, making up her mind to it, “for she had her feet swathed in a Cashmere shawl of pinks and oranges, and draped over her knees a very fine silk wrap, undoubtedly made of the same type of silk as the piece she gave Amabel, but in a shade of deep blackberry, and lined with—well, sables.”

“That is not amusing, Christabel, and I am astonished at you.”

“No, Mamma, it really was!” cried Amabel. “Immensely fine furs, and she had besides another wrap of them round her shoulders, only she mostly kept that thrown back, for she was wearing the most glorious Cashmere shawl I have ever seen!”

“Yes. It was all deep crimsons and blues, with a deep blue edging, a lovely thing, Mamma,” agreed Christabel, looking gratefully at her sister.

“Well, I am sure I beg your pardon, my dear. –Sables? Indoors? At midday?”

“Yes, and the wrap about her shoulders was obviously intended to be worn with the fur out, and Mamma, you will never guess what colour the lining was, with all that blackberry silk, and the blues and crimsons of the shawl!” cried Amabel.

Mrs Maddern and Mrs Parkinson looked at her with a wild speculation in their eyes.

“It was a terribly harsh acid yellow, a glorious stuff, but truly, Mamma, the effect was—was—bizarre!”

“I should say so!”

“She must be entirely lacking in taste,” said Mrs Parkinson numbly.

“Oh, exactly, ma’am,” agreed Amabel, “for she was besides hung all over with jewellery, none of which matched! That is to say, it did not tone with her garments, but as well, none of the pieces matched each other!”

The two older ladies exchanged glances.

“Foremost amongst it,” said Christabel on a very dry note, rising, “was the most magnificent rope of pearls I have ever seen in my life. Each one the size of a large pea, perfectly matched, and I dare say two yards in length, for she had them knotted over the bosom and they still fell to below her waist when she stood. –I think I will just go and check on the twins, Mamma, I have a feeling that in their over-excited state they will be too much for Miss Morton.” She went over to the door and added with a twinkle: “And I also have a feeling that if Miss Morton tries to insist on their consuming bread and butter this evening, the results will be fatal!” She went out, smiling.

“She really liked her,” ventured Amabel. “I wish you had come, Dorothea, for they were all laughing and talking and so on, and I must confess that more than half the things Mrs Urqhart said I did not understand, but I had expected that: but more than half the things Christa and Hildy, and Paul and Gaetana said I did not understand either!”

“Never mind, dearest. If you go again I shall come: she sounds very entertaining, indeed, and most exceeding good-hearted.”

“Indeed she is, and so kind!” said Amabel, smiling and sighing. “She would give Bunch that dagger when she admired it—and I will say this for our little cousins, they are not the type of children who have been brought up to hint in a nasty way for gifts!”—the ladies all nodded—“but you know, it was on a high shelf with its own stand and really, I fear it may be a collector’s piece.”

Mrs Maddern bit her lip. “We must do something for her.”

“Yes. I—I think it might be wise to invite her to dine, Patty,” faltered Mrs Parkinson.

“Yes,” she said determinedly: “I shall do it. We shall not be a large party, just ourselves and— Amabel, you have not said, were the two gentlemen there?” she gasped.

“No: they had rid out. Lord Lucas was most keen to see the countryside hereabouts. And I think Mrs Urqhart had encouraged them to go,” she said with a twinkle, “in order to have her guests quite to herself! She was enchanted with the children, Mamma, and told us she misses seeing her own grandchildren dreadfully!”

Mrs Maddern produced a cambric handkerchief and blew her nose solemnly. “I shall wear my good bronze silk for the dinner,” she pronounced.

“In that case I shall wear my lilac, it is more than time we went into half-mourning, and Dorothea, I absolutely forbid you to appear at the table in black!” said her mother, ending on a fierce note.

“But I—I do not have any other gowns, Mamma,” she faltered.

Mrs Parkinson had quite forgot that: what garments her poor daughter had brought back from Ostend with her had been in tatters, the Captain having sold all his wife’s finery for pocket money to dice away, and Dorothea having sold all the rest that were saleable for milk and bread.

“You may wear a white muslin of Christabel’s, my dear, you are very much of a height, and similar figures,” said Mrs Maddern firmly.

Mrs Parkinson repressed a sigh: Dorothea had been used to have just such an excellent figure, but on her return from Belgium she had been terrifyingly thin, and had still not regained all of the lost weight. She tried not to think of how Christabel’s dress would sag round the bust on her poor daughter.

“And,” continued Mrs Maddern, “if you insist, black ribbons, though personally I feel that lilac or grey—”

“Please, black, dear Mrs Maddern,” said Dorothea in a tiny voice, blushing very much.

“Just as you wish, my dear. Now, run along, girls, I declare I feel quite exhausted after hearing about the elephants and camels. I think I will put my feet up,” decided Mrs Maddern. “ Wilhelmina, my love, do you take that sofa, should you care for it.”

Mrs Parkinson of course cared for it: the two ladies had been putting their feet up in Mrs Maddern’s boudoir every afternoon since she had arrived.

Amabel rose and quietly drew the curtains, and she and Dorothea went out.

It had not seemed to Dorothea that Amabel was overtired by the visit, but to her surprize she suddenly said in a choked voice, as they neared her room: “Christa is so lucky! I do so wish I could wear pink and blue, like her and Luh-Lady Charleson!” A tear trickled down her round cheek.

Dorothea put an arm round her waist. “Silly one,” she said gently. “You are the prettiest girl I know. I have never seen anything half so lovely as you in jonquil or white.”

Amabel burst into sobs. “They are not as puh-pretty—as puh-pink or buh-blue!”

Dorothea led her into her bedroom, sat her down on the bed, and putting her arms round her, let her have her cry out without saying anything more except: “Hush”, and “There, there.”

“Well!” said Mrs Urqhart happily to her two young gentlemen on their return from their ride. “We have had the happiest day! Those children are delightful, you cannot imagine! Just fancy, dear Noël, red-headed twins, very near the colour of Bapsee’s carrot hulwa, you have never seen anything like, and one is a girl and one is a boy!”

“And are they the terrors they are reputed to be, ma’am?” he asked with a smile.

“Nothing of the sort! Two lively and intelligent little dears! –My, ain’t it pity as they has to grow up?” she added on a glum note.

“Er—true. Into such as we,” he said with a wink at his friend.

Mrs Urqhart gave a little scream and—for her fan was not to hand—slapped his arm playfully with the flat of her palm. “Any ma would be proud to have either of you for her son, silly boy! –And do not put that prim look on your face, Noël Amory: I knows as you was fishing!”

Sir Noël and Lord Lucas laughed.

“I was thinking, my dears, do you suppose their mamma would permit the young people to come over for a dinner and little dance?” she said on a hopeful note.

The two young men studiously avoided each other’s eyes.

“No, I s’pose not,” she said dolefully. “Only I would so love to see this old house filled with young things!”

Sir Noël sat down beside her on the sofa and unaffectedly hugged her. Lord Lucas, coming from the very stiff and proper home of Lord and Lady Hubbel, regarded this behaviour in some amaze, though he had already realized that Noël and his Aunt Betsy were on terms of perfect affectionate understanding.

“I shall ask them all to a luncheon party myself, Aunt Betsy, I am sure there can be no objection to that.”

“No,” she agreed, sniffing.

“And you will have young ladies and gentlemen to your heart’s content!”

“Aye. –Two of the ladies did not come,” she revealed, sniffing a bit: “the poor pretty little widder—well, she did look tired, I thought, yesterday at the ruin, so that wasn’t surprizing, but that other very proper young lady, she never came, neither.”

“Miss Dewesbury?” said Lord Lucas uncomfortably. “She— Her mamma is—” He broke off, gulping.

“Don’t tell us,” she said glumly. “I dare say your mamma wouldn’t let you come, neither, if she knowed what your friend’s aunty’s really like, eh?” she added shrewdly.

Captain Lord Lucas flushed up. “My mamma has nothing to say to my comings and goings any more,” he said stiffly.

Sir Noël gave him an ironic look: he knew damned well that Lady Hubbel would have had ten fits could she have laid eyes on Aunt Betsy, and that Lord Hubbel would have given poor old Lucas an icy scold for lowering the family standards, or some such damned balderdash. He was only too well aware that, though the Army career had been decided on by his stern papa and did not reflect his own wishes, Lucas had fled to the regiment as a bird to its nest, and for years, on various excuses of varying validity, such as being on duty, or posted to distant parts, had managed to see as little of his stiff-necked family as was possible within the bounds of decency.

“Absolutely, old fellow,” he agreed on a dry note. “Besides, Aunt Betsy, even if we do not have all of them to visit, we shall go on in a jolly way amongst the three of us!”

“But I thought as you was wishful to see ’em, Noël?” she cried in amaze. “You and Lucas both! –Oh, drat, now I have gone and called you Lucas!” she added crossly.

Lord Lucas smiled suddenly. “You must call me Lucas as much as you please, ma’am, I should like it of all things.”

“Well, if you is sure? Because you is the son of an earl. Though mind you, I’ve met lords and ladies in Calcutta: we ain’t so fussy in India, you know!”

He nodded, and smiled. “I should be honoured.”

“Well, then, Lucas, me dear, I will! But Noël, does pretty little Miss Ainsley not favour you, after all?”

“No,” admitted Sir Noël glumly. “I asked her to come for a drive with me, and she said straight out she had rather not because she did not want to give me any false hopes.”

“Oh, Lordy!” she cried in distress. “Well, what about your one, Lucas, me dear? Now, which one is it? Noël told me it was a gal with a fine upstanding figure— Land save us, not the pretty widder that did not come?” she cried.

“Er—no, ma’am,” he said, rather startled. “Would you say she had a fine figure?”

“Certainly, my boy, is you blind?” she replied with a rich chuckle.

“He admires the one with the bosom, Aunt Betsy,” Sir Noël reminded her.

“Oh, the handsome lady what’s got all the cousins and sisters in charge!”

“Miss Maddern,” said Lord Lucas faintly.

“Lordy, me love, she’d run rings round you!” she cried.

Lord Lucas gaped at her.

Mrs Urqhart nodded firmly. “Indeed and indeed she would. Now, I’m an old woman without no book-learning, but I knows young ladies and gents! She’d do it nice, mind, but you wouldn’t never have your soul to call your own, with that lady!”

“Don’t know that I’d want to,” he muttered, staring glumly at her magnificent Persian carpet.

“Of course you would, my lovey! Well, not in the first few months, maybe!” she said with her rich chuckle. Lord Lucas turned puce but Mrs Urqhart, though secretly amazed at this phenomenon, affected not to notice it. “No, take my advice, dear lad: take the widder,” she said.

He jumped violently, and goggled at her.

“Even though she ain’t got the bosom,” noted Sir Noël on a sour note.

“Now that’ll be enough out of you!” said his Aunt Betsy, laughing, and slapping his thigh for a change. “Has she got a baby?”

“Er—a little girl aged about one year, I believe, Aunt Betsy,” he said faintly. ‘‘Why, in God’s name?”

“She’ll have been lettin’ it suck,” she said wisely, nodding. “That’s too old, of course, but sometimes it do pacify ’em, and she don’t look to me like the sort of young mother as would refuse a babe the tit.”

Sir Noël, though trying not to laugh, looked at his friend’s puce cheeks and took pity on him. “Aunt Betsy, you’re putting us two unmarried gentlemen the blush!”

“Rubbish, me dear! It explains why the bosom’s a bit flat: when the baby lets her alone, she’ll fill out a bit, you’ll see!”

Sir Noël bit his lip, failed to control himself, even though poor Lucas was still glowing like the sunset, and went into a gale of laughter.

“That’s better!” she said, beaming.

“Always—thought—they got bigger—at that time!” he gasped.

“Not if there ain’t any milk in ‘em, you fool!” she said loudly and cheerfully, and he went into further paroxysms.

Lord Lucas got up abruptly. “I think I’ll go and change before dinner, if I may, ma’am,” he said, bowing.

“Poor lamb,” she said in his absence. “Ain’t he never had a woman, then?”

Her nephew wiped his eyes. “I have no notion, my darling, but he’s around my age: he must have.”

“Don’t count,” she said, shaking her head. “It’s character what counts, not age. Why, my Pumps was twenty-seven when he first done it, and that was on our wedding night.”

“Good God,” he said faintly. “I was—”

“Seventeen,” said his Aunt Betsy immediately. “And it were in my hay loft as you done it, with that cheeky Rose Marie Cummins, and don’t I know it!”

Sir Noël goggled at her.

“Well, she had Timmy, too,” she said reminiscently. “But me and Pumps, we married her off right smart to that Jem Higgs, and afore you gets to silly recriminations, he’d had her too, so the brat coulda been your’n or Timmy’s or his, and if he didn’t care, no more did we!”

“God,” he said, passing his hand over his face.

“Young gents never think of the practical side of the thing: not at that age.”

“No. But she—” He broke off.

“Oh, I know as she wanted it, me dear. But as to your friend Lucas—well, if he can’t talk about a woman’s breasts without blushing, it stands to reason, dunnit?”

“He— I suppose, in the regiment, one talks a lot of damned balderdash that’s less than half true.”

“Well, if you’re decent boys it’s less than half true!” she said vigorously.

“Yes.” Noël swallowed. “My Colonel was always rather keen on young officers not marrying when they couldn’t support a wife properly. I suppose in a way it was sensible, but in another way—

“Aye: silly man, too old to remember what it was like when it were so hot he couldn’t hardly bear himself.”

“Yes. –Aunt Betsy, I do beg of you, don’t say anything like that in front of poor old Lucas!”

She gave him a tolerant smile. “Never fear me, me love, I ain’t doolally, I only looks it!”

Sir Noël went into another paroxysm, having to mop his eyes.

“He’s a nice boy—that ma and pa of his may be lords but they don’t sound like much chop,” she said thoughtfully. “I think as we might encourage the young widder woman, deary. See how it goes on.”

“Yes—well, so long as her bosom plumps up!” he said with a gurgle. “Though Lucas has admired Miss Maddern since first setting eyes on her, you know, Aunt Betsy,” he added uneasily.

“I dare say. But he don’t know what he wants. Like I said, she’d run rings round him. Now, I ain’t saying that don’t sometimes work out real good, but there’s other times when the woman ends up a nag and the man ends up miserable! And he’s a man what would like to fancy himself the master in his house, even when he ain’t!”

“Yes,” he said, eyeing her in fascination and wondering what sort of a man she’d sum him up as—and, on the whole, not daring to speculate on it.

“Run along, dear boy, and get yourself into your pretties for dinner, for I dare say as neither of you is so lovelorn as not to fancy your dinners! But I must say,” she added with a sigh, “that I won’t be able to eat a crumb, I’ve stuffed meself on the damned woman’s sweetmeats again!”

Sir Noël rose gracefully, and kissed her cheek. She immediately planted a smacking kiss on his in return, and he went out, smiling.